The Inter-War Years

The War Department created a new 1st Pursuit Group between late April and mid-August 1919, when it dispatched two-man cadres of the 27th, 94th, 95th, and 147th Aero Squadrons to Selfridge Field, Michigan. New recruits and veterans from other flying units arrived to assume their places in the squadrons, and by late summer the process was complete. The Army activated the 1st Pursuit Group on 22 August 1919. The unit then took its place as one of the three group-level organizations that constituted the Army's air arm for most of the next decade. Like the 3rd Attack and the 2d Bombardment Groups, the 1st Pursuit spent most of the next twenty-two years testing aircraft and tactics developed to exploit the potential of the aerial weapon.

The group's initial tour in Michigan lasted less than ten days. On 28 August the four squadrons departed by train for Kelly Field, Texas. The newly organized group headquarters, under the command of Captain Arthur E. Brooks, left Selfridge for Kelly two days later. For the next three years the group remained in Texas, where it operated the Advanced Pursuit Training School.

The leaders of the Army Air Service knew that the organizational and operational lessons learned during World War I would shape postwar activities, but in the haste to demobilize after the war the Army broke up units without giving adequate thought to its future needs. As the organizational situation stabilized at the end of the summer of 1919, the Army began to devise better considered defense plans, and it also recognized that the proper application of the lessons of the war required a carefully planned training program. The decision to use the 1st Pursuit Group as an Advanced Pursuit Training School" reflected this thinking.

The Army used the pursuit school to build an effective fighter force in stages, beginning with the fundamentals of flying and culminating in group-strength fighter maneuvers. The course of instruction for pilots at Kelly consisted of a twenty-week program of classroom and in-flight training. Topics covered included squadron, group, and air service history, the history of aircraft and aero-engine design, development, and maintenance, aeronautical theory, military and aerial strategy and tactics, weather, navigation, operational procedures, and organizational theory and practices. Pilots received hands-on experience in aircraft and engine maintenance. They also flew a 72-hour program that covered formation flying, aerobatics, air-to-air and air-to-ground gunnery, reconnaissance and patrol tactics, and emergency procedures. In addition, pilots served liaison tours with bombardment and attack units and with infantry, cavalry, armor, and artillery formations to improve intraservice understanding and coordination. Pilots also made a number of tethered and free lighter-than-air flights.

After completing this part of the syllabus, the pilots joined a squadron, where their training entered another stage. They spent somewhat less time in the classroom, more in the air. When the pilots learned to fly and fight as part of a larger unit, training progressed to the group level. This phase of the course included some group-strength formation flights and squadron-versus-squadronair combat, but the pilots again returned to the classroom for work in the fundamentals of officership, command, management, and staff activities. While the Advanced Pursuit Training School trained the pilots, the group's mechanics and support personnel kept busy with their own course of classroom and field work. They practiced their trade by working on aircraft used to support the flight training syllabus.

The 1st Pursuit Group's work at the Advanced Pursuit Training School, initially at Kelly and later at Ellington Field, Texas, established a solid foundation that the group built on during the next decade. During the 1920s the group was the Army Air Corps' only group-level pursuit organization. As such, the Army repeatedly called on it to evaluate new aircraft designs, test equipment under a variety of operating conditions, demonstrate aircraft and unit capabilities, and practice advanced tactics during Air Corps and Army maneuvers. The group also flew numerous public relations flights throughout the eastern and mid-western United States. The years in Texas forged the group into a competent, cohesive unit. The group used this training as the basis for more demanding projects undertaken during the Twenties.

The 1st Pursuit Group prepared to return to Michigan in late June 1922. It still consisted of four squadrons, although the 14 7th had been redesignated the 17th Aero Squadron on 3 March 1921. The air echelon, consisting of the 17th, 27th, 94th and 95th squadrons and led by the group's commander, Major Carl Spatz (later Spaatz) departed Ellington Field on 24 June 1922. The ground component followed on 27 and 28 June. The long aerial deployment was a novelty, and the public and the press followed the group's progress closely. The aircraft arrived at Selfridge Field on 1 July 1922.

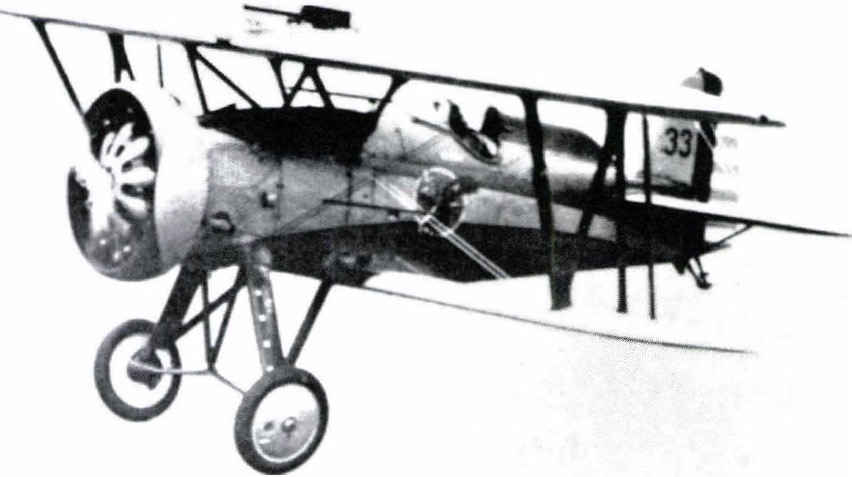

Selfridge served as the group's home for many years. The field was situated on i:t 641-acre site located northeast of the city of Mount Clemens, a suburb of Detroit. It was named after Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge, one of the Army's first pilots, who died in the crash of a Wright Flyer flown by Orville Wright on 17 September 1908. The site was reclaimed swampland, and poor drainage plagued the field for years. Nonetheless, the group settled into its new home and began preparations for an event that became a hallmark of the 1st Pursuit.7 The National Air Races took place at Selfridge Field from 7-14 October 1922. Included in the program was the first running of the Mitchell Trophy Race. Brigadier General William Mitchell donated the John L. Mitchell Trophy to the Air Service in memory of his brother, lost in action during World War I while serving with the 1st Pursuit Group. Mitchell aimed to stimulate the development of better pursuit aircraft, and the races, held from 1922-1930 and from 1934-1936, became a key proving ground for new pursuit designs. The first Mitchell Trophy Race seems to have been open to all qualified entrants, but the entry criteria soon became more restrictive. To be eligible for the Mitchell Race, a pilot had to be a Regular Army officer and a member of the 1st Pursuit Group who had served at Selfridge for at least one year and had accumulated at least 1,000 total flying hours. A final qualification made the race especially significant for the group's pilots: a pilot could fly in only one Mitchell Trophy Race. Lieutenant Donald F. Stace of the 27th won the first Mitchell race. He made four circuits of the twenty-mile course in his Thomas-Morse MB-3 at an average speed of 148.1 mph.

The Mitchell Trophy Race provided a moment 9f excitement each year, but most of the group's regular operational activities throughout the decade were far less glamorous. As the Air Corps' only pursuit group, the War Department took special pains to ensure that the 1st maintained a high state of readiness. It conducted quarterly inspections and mobilization tests during 1923, 1924, and 1925. The units performed well during these tests, but to maintain its edge the group itself conducted its own regular inspections and practice alerts. These types of activities have long dominated the peacetime operating schedule of all types of military organizations; the interwar 1st Pursuit Group was no exception.

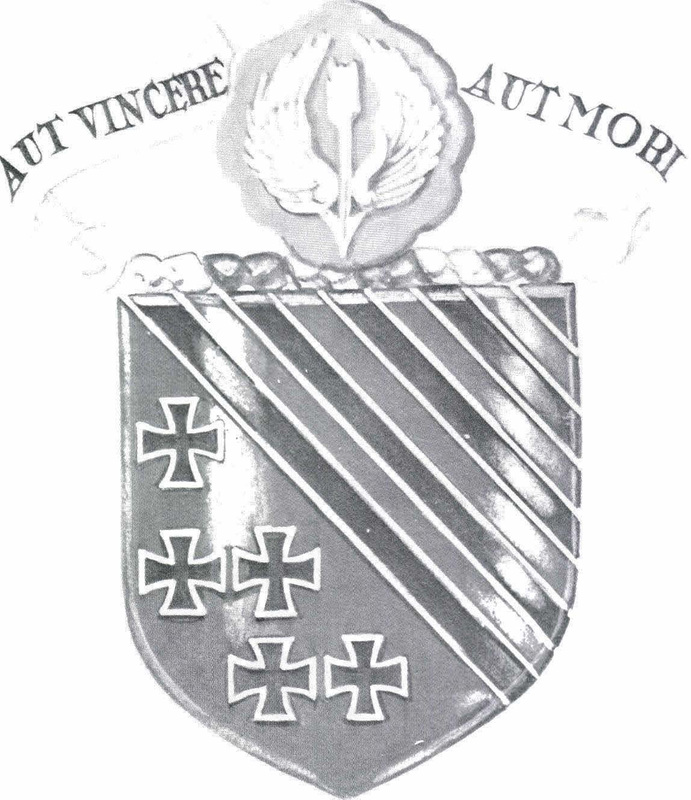

In 1924 the War Department sanctioned unit emblems. On 21 January 1924, the Adjutant General approved the emblem of the 1st Pursuit Group. The design of the device reflected the unit's history. The colors of the shield, green and black, represented the original Army Air Service. The five stripes stood for the group's five original squadrons, and the five crosses symbolized the group's five major World War I campaigns: Champagne-Marne, Aisne-Marne, St Mihiel, Verdun, and Meuse-Argonne. The colors of the crest, with its golden winged arrow on a sky-blue disc, were the colors of the Army Air Corps. The crest bore the group's motto: "Aut Vincere Aut Mori" - "Conquer or Die." Revisions made in 1957 deleted the crest and added the scroll at the base of the shield.

The Adjutant General also approved unit emblems for the squadrons. The "Great Snow Owl," white on a black background, became the official emblem of the 17th Pursuit Squadron on 4 March 1924. The next day the World War I-vintage "Kicking Mule" emblem was officially assigned to the 95th Pursuit. On the same day, 4 March, the 27th's "Diving Eagle" became a "Diving Falcon," because the War Department did not want to appear to be endorsing a brand of beer.

Commercial considerations forced the War Department to change the emblem of the 94th. During the early 1920s Eddie Rickenbacker decided to produce a line of automobiles that bore his name. Rickenbacker adopted, as the company's logo, the hat-in-the-ring device the 94th had used as a unit emblem during the war. Again in an effort to avoid appearances that it was promoting a product, the Adjutant General's office decided, on 6 September 1924, that the 94th would use the Indian-head device formerly used by the 103rd Aero Squadron, a World War I unit formed when the members of the Lafayette Escadrille transferred to the Army Air Service after the United States entered the war. Even though the Rickenbacker was not a commercial success and the company soon went out of business, the 94th continued to use the Indian-head insignia until 1942.12

The group also opened a satellite facility in 1924. On 18 May thirty enlisted men left Selfridge for Oscoda, Michigan, to establish an "Aerial Gunnery Camp" for the 1st Pursuit Group. Facilities at the camp were spartan at first, but during the course of the next decade the group made numerous improvements at the site. Such improvements were necessary, because the squadrons of the 1st Pursuit returned to Oscoda regularly for gunnery practice against towed and ground targets. These deployments usually included one of at least squadron strength during January or February, intended to test aircraft in severe winter conditions, and a larger deployment during the spring devoted to gunnery practice. The group also regularly rotated squadrons through Oscoda to prepare them for special tests or maneuvers.

Beginning in about 1925, the group participated in exercises, demonstrations, and maneuvers, events the War Department used as combined training and public relations exercises. Public and congressional interest in aviation was high. The group flew fast, nimble, pursuit planes that attracted the attention of earth-bound taxpayers wherever they appeared. At the same time, the War Department wanted to test evolving doctrines and tactics that would enable the air arm, especially tactical aviation, to work effectively with other branches. As a result, the group's Selfridge training schedule often aimed to prepare the unit for demanding summer and fall activities.

The 1925 training cycle was typical. Between May and October the group completed four formal tactical inspections and participated in a mobilization test on 4 July that saw it dispatch planes to Alpena, Oscoda, and Frankfort, Michigan, Washington, DC, and Youngstown, Ohio. On 26 February, group commander Major Thomas G. Lanphier led a flight of twelve PW-8 aircraft from Selfridge to Miami, Florida, in an attempt to set a dawn-to-dusk flight record. The flight reached Macon, Georgia, by mid-afternoon, when bad weather forced the planes to the ground. The aircraft finally reached Miami on 2 March. The War Department made use of the contingent's presence on the East Coast to put on a demonstration for Congress and the press.

The demonstration was held at Langley Field, Virginia, on 6 March. A static display on the flightline enabled the assembled congressmen to examine the planes. The aerial portion of the demonstration, which occupied most of the afternoon, used as its scenario a simulated attack on a battleship silhouette. The 1st Pursuit's twelve aircraft opened the attack by strafing the silhouette and dropping light bombs. The fighters then laid a smoke screen to cover the attack of heavy bombers and attack aircraft, which the fighters protected and attacked in turn.

The spectators seemed duly impressed with this demonstration, but some contact with members of Congress brought the group rather less favorable attention. On 26 March 1925 Lieutenant Russell Minty's aircraft failed to clear a stand of trees and crashed shortly after takeoff from an airfield near Uniontown, Pennsylvania. The pilot escaped injury but his passenger, a Pennsylvania congressman, was not so lucky. He was badly cut and bruised and suffered a broken collarbone and several broken ribs. The congressman's reaction to this mishap is not recorded, but the group diary noted Minty's transfer to non-flying duties on 27 March.

The unfortunate Lieutenant Minty had a bad year in 1925. Returned to flying status, he joined five other 1st Pursuit Group pilots detailed to fly from San Francisco to New York to test a new transcontinental air-mail route. The group left Selfridge on 15 July. On 31 July Minty escaped injury when his P-1 crashed and sank in the Des Moines River during a night flight from Cheyenne, Wyoming, to Chicago. The circumstances of the lieutenant's mishap served as an unfortunate precursor of the group's later involvement with carrying air mail.

An inspection conducted by Major General Mason M. Patrick, Chief of the Air Service, on 29 January 1926 ushered in another busy year for the 1st Pursuit Group. After winter maneuvers at Oscoda, the group deployed a detachment of eighteen aircraft (eight PW-8s, seven P-ls, two P-lAs, and one C-1) to Wilbur Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, on 19 April to participate in Army Air Service maneuvers. The purpose of this exercise was "to train the Air Brigade Staff and the lesser Staffs in the technique of air force units during concentration of ground forces up to a point just before the actual meeting of the ground forces." It was the second of three such exercises: the first, in 1925, simulated an attack on the coast and focused on the staff work required to concentrate aircraft at the point of attack; the 1927 exercise simulated air operations during the land battle. The 1926 maneuvers began with a command post exercise. The flying units based subsequent tactical operations on situations that had developed during the first phase.

In addition to the 1st Pursuit's seventeen aircraft, the Army Air Service detachment at the maneuvers included thirteen aircraft from the 2d Bombardment Group and twelve planes from the 3d Attack Group. Two aircraft formed a "Provisional Observation Group." The main tactical problems covered during the operations phase included pursuit patrols versus bomber and attack aircraft, with special emphasis on the development of pursuit tactics against both types. The group also worked on offensive tactics, including rendezvous, attack formations, and escort tactics. During seven days of flying the 1st Pursuit Group flew 154 sorties and 186 hours. In his report on the maneuvers, Brigadier General James E. Fechet, Air Service Chief of Staff, expressed concern that pursuit tactics, which he feared were becoming too inflexible, exposed the pursuit planes to defensive fire for too long. The maneuvers also pointed out that the units needed more practice in long-range formation flying.

The maneuvers detachment returned to Selfridge on 1 May 1926. Later that month, the group sent three P-ls, three pilots, and twenty mechanics to Camp Anthony Wayne, Pennsylvania, where they served as part of the Air Corps (the Air Service became the Air Corps on 2 July 1926) Demonstration Detachment at the Declaration oflndependence Sesquicentennial Exhibition at Philadelphia. The other members of the group continued to carry on training at Oscoda and Selfridge throughout the summer. On 26 September six pilots flew their P-ls to Kelly Field, Texas, for temporary duty in support of the filming of the movie Wings.

The group's activities peaked in 1927 and 1928. Increasing interest in the effects of cold weather on operations took twelve aircraft to Canada from 24-30 January 1927. The army wanted to "determine the limitations of aircraft and equipment when operating under deployed conditions in a severe climate" and to test various types of skis for use on aircraft. The Canadian government welcomed the test contingent as a good-will gesture, and the War Department approved the flight on 23 January. The group deployed thirteen aircraft (six P-lAs, four P-lBs, two P-ls, and one Douglas C-1 transport), thirteen pilots and six mechanics from Selfridge to Ottawa the next day.

Conditions in Canada proved ideal for the test. The aircraft arrived in the midst of a blinding snowstorm, and "the poor visibility and the difficulty of keeping the landing area clear of pedestrians somewhat hindered the Flight in landing." The landing area on the Ottawa River was covered with twenty inches of snow, and the aircraft's rear skids broke through the crust, causing damage to each of the aircraft. Canadian mechanics helped install large disks on the tail skid to support the aircraft.

Temperatures got no lower than 20°F during the night of 24-25 January, but this was enough to chill the engines thoroughly. Mechanics filled them with hot oil the next morning, but they were still too cold to start. "Hot bricks placed in the air intakes close to the carburetor, used to vaporize the ether priming" did not work well either.

The mechanics finally borrowed a fire hydrant defroster from the Ottawa Fire Department, forced steam into the engines, and got them started. The detachment commander noted with interest, however, that the P-lBs equipped with self-starters turned over much more readily on the cold morning.

The Canadian flight's luck with the weather continued. The aircraft departed Ottawa in the early afternoon of 25 January. They ran into another blinding snowstorm, landed on the Ottawa River, took off when the storm cleared, landed when another squall developed, then took off a third time. The 100-mile flight took about two hours, and the section finally arrived at Montreal. Mechanics drained the water and oil from the engines, but that still left the pursuits poorly prepared for the -20°F they faced the night of 25-26 January. Three-man crews, working ninety minutes on each aircraft, got all planes started the next morning.

Flying on the 26th was uneventful, but the thermometer dropped to -22°F that evening. The crews delayed the takeoff of their flight to Buffalo, New York, because "it was doubtful whether it would have been possible for the pilots to have withstood the cold for four hours in their present type of flying equipment.1125 By about 1300 eleven of the twelve pursuits were ready to depart, but a sticking carburetor prevented the twelfth from starting. Nine aircraft took off about 1400, but a storm forced them down near Fisher's Landing, New York. The aircraft "taxied to a position in the shelter of the boat house and wharves on the shore of the little cove." The storm did not abate, so the pilots stayed in Fisher's Landing overnight. The nine-plane flight reached Buffalo on 29 January.

In the meantime, the three aircraft left behind in Montreal took off at about 1530 on 28January, but poor visibility forced them to turn back. They took off again at about 1100 the next day and reached Alexandria Bay, New York, before a radiator leak in one plane forced the flight down. The three took off and reached Woodville, New York, when one aircraft's broken oil line forced them down again. Two continued while the pilot of the damaged aircraft repaired the oil line. The two-plane flight landed near Irondequoit Bay when a radiator overheated. On takeoff the plane that suffered the radiator leak lost its engine. The three planes finally staggered into Selfridge between 30 January and 1 February. The nine planes from Buffalo arrived at Selfridge on 30January.

The flight commander's recommendations came as no shock to those who followed the flight's progress. The Air Corps needed aircraft with engine block heaters and self-starters, a stronger tail skid for its aircraft, and a warmer and more comfortable winter flying suit.

The 1927 maneuver/demonstration cycle began on 27 April, when Captain Hugh M. Elmendorf, commander of the 94th, led a five-plane flight from Selfridge to Bolling Field, DC. The flight then proceeded to Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland, where mechanics added smoke generators and the pilots learned how to lay the smoke in conjunction with armor and infantry attacks. This flight then made its way to Pope Field, North Carolina; Atlanta, Georgia; Fort Benning, Georgia (where it put on tactical demonstrations for the instructors and class at the Infantry School); Mansfield, Louisiana; Galveston, Texas; and finally Kelly Field, Texas, where the Army held its 1927 maneuvers.

A second demonstration flight of eight P-ls, led by Captain Frank H. Pritchard, left Selfridge on 3 May. This group flew demonstration flights at Fort Riley, Kansas, and Fort Sill, Oklahoma, before arriving at Kelly Field on 10 May. The next day the group launched eighteen more P-ls for Kelly, this detachment led by Major Thomas G. Lanphier, the group commander. The detaehment left Selfridge at 0630. It arrived at Kelly at 1815 after making two intermediate stops, where waiting group mechanics serviced the aircraft. When the maneuvers began on 15 May, the 1st Pursuit Group had thirty-one P-ls deployed at Kelly Field, with thirty-one pilots, twenty-one mechanics, and twelve support specialists.

During seven days of maneuvers (15-21 May), the group flew ground attack, bomber attack, bomber escort, air superiority, and defensive missions. In addition, the group participated in a day-long series of demonstration flights for visiting dignitaries on 21 May. Umpires noted that "the operations of the First Pursuit Group as a whole during these maneuvers were very good, " but in his critique Brgadier General James E. Fechet, the air commander at the maneuvers, warned that "conditions for air operations here were almost ideal and would not necessarily be obtained in actual operations. In other words, the airplanes here were operated under conditions which were better than we could expect in warfare." Under these conditions the group flew 236 operational and 23 demonstration sorties and approximately 400 hours.

The group returned to Selfridge on 25 May and had barely settled in when it undertook another large-scale demonstration flight. On 12 June the group flew twenty-two P-ls nonstop from Selfridge to Bolling Field to act as an escort for Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh on a tour through several east coast and mid western cities. Stops on the Lindbergh tour included New York, St Louis, Selfridge, Ottawa, and Buffalo. During each of these visits the aircraft of the 1st Pursuit Group provided demonstration flights and static displays. The escort detachment returned to Selfridge on 8 July, but the group had not seen the last of Colonel Lindbergh. On 4 November 1927, he reported to Selfridge for fourteen days of active duty training with the group. His training included a trip to the Oscoda range.

Not long after the Lindbergh escort flight returned to Selfridge, the 1st Pursuit Group bid goodbye to one of its original units. On 31 July 1927 the War Department inactivated the 95th Pursuit Squadron and transferred it to March Field, California, where it was activated on 1 June 1928 and attached to the 7th Bombardment Group. The squadron soon traded its pursuits for attack aircraft, and in World War II the squadron, now designated the 95th Bombardment Squadron, flew its B-26s in the Mediterranean theater of operations, where the P-38s of the 1st Fighter Group often escorted them to their targets.

The hectic pace of the group's activities continued during 1928. Training continued to occupy most of the group's time. There were no maneuvers in 1928. Instead, the group deployed twenty-two P-ls, five C-ls, twenty-six officers and thirty enlisted men under Major Lanphier, group commander, on a twenty-four day demonstration tour to the Army's service schools. This group left Selfridge on 29 April and proceeded to Bolling Field, where it added four pursuits previously sent to the Edgewood Arsenal. Those aircraft participated in an Air Corps demonstration at Bolling on 29 April and then flew to Langley Field for a series of tactical demonstrations. The Langley program included static displays, mock combat between pursuits, bombers, and attack planes, aerobatics, ground attacks, and an aerial review.

From 5-22 May, a thirty-four plane (twenty-six P-ls, eight C-ls) detachment from the 1st Pursuit Group visited the Army's major posts and schools. The tour took the group from Langley to Fort Bragg; Fort Benning (Infantry School); Maxwell Field (Air Corps Tactical School); Fort Sill (Artillery School);Fort Riley (Cavalry School); and Fort Leavenworth (Command and General Staff School). Each stop featured a similar program: static displays, acrobatics, aerial reviews, and tactical demonstrations with the service arm the school specialized in. Eight of the P-ls returned to Selfridge on 22 May, but eighteen flew to Des Moines, Iowa, for more demonstration flights. This detachment returned to Selfridge on 26 May. During the tour the group flew 765 sorties and more than 1,430 hours.

While the Des Moines flight involved an unusually large contingent of aircraft, it typified another activity the 1st Pursuit Group participated in repeatedly throughout the 1920s. Many communities, large and small, built municipal airfields during the decade. These airfields often opened with an air show, a:r;i.d the Air Corps, aware of the opportunity for publicity these shows offered, responded readily to local requests for an Air Corps display at the opening. Since the pursuits had long since proved they could get into and out of even the roughest landing field, the 1st Pursuit Group frequently sent small detachments to airport openings. During the summer of 1928, these missions took group aircraft to many sites throughout the mid west.

The group's training followed established patterns through the last year of the decade. The largest deployment of 1929 saw the group send fifty pursuits to central Ohio for maneuvers in May. While operations at the maneuvers were conducted without major incident, a critique of the performance of the pursuit aircraft noted that "it is quite obvious our training methods and our tactics as applied to pursuit, are not now satisfactory." 39 The report repeated some of the criticism levelled at pursuit tactics during World War I: pursuit units placed too much emphasis on tight formations, too little on effective attack tactics. As a result, only the lead plane in a formation delivered aimed fire. The rest fired on his cue, spraying a cone of bullets in the general direction of the target. These tactics forced wingmen to spend too much time watching the leader, too little watching for enemy aircraft. Other activities during 1929 followed similar patterns: inspections, demonstration flights, equipment tests, Oscoda deployments, and airport openings.

Overall, the Twenties were a productive decade for the 1st Pursuit Group. It responded well to the challenge of being the Air Corps' only group-level pursuit organization, and developed a reputation as a dynamic, well-trained force, prepared to respond skillfully to the operational demands the War Department placed on it. The group maintained a high degree of organizational stability. It even enjoyed the benefits of using tried and tested, if somewhat dated, equipment. While the unit flew a mix of obsolescent World War I aircraft during its stay in Texas, by 1924 it had converted to the Curtiss PW-8/P-1 series it used for the remainder of the decade.

The 1930s produced a different set of challenges. During that decade, the group introduced at least six new aircraft types into the Air Corps inventory. It also provided cadres for newly formed squadrons and groups. But even as it carried on these activities, the pace ofits regular training activities continued unabated.

The 1st Pursuit Group began the decade with a cold weather test flight that forced a detachment to operate in the face of extremely difficult conditions. On 7 January 1930 the group's mechanics positioned eighteen P-ls, two C-9s, a C-1 and an 02-K observation aircraft on the ice of Lake St Clair, adjacent to Selfridge Field, in preparation for the takeoff of the 1930 "Artie Patrol Flight." The primary purpose of the flight was to "test the efficiency of planes, personnel, and equipment under the most severe winter conditions." A secondary object of the flight was to "obtain first-hand experience on the value of shortwave radio in connection with Army Air Corps operations in remote sections and covering long distances." To this end, one of the cargo planes carried a complete radio set. The flight would proceed from Selfridge to Spokane, Washington, and back via stops in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and North Dakota.

The flight was scheduled to take off on 8 January, but a sleet storm made even the iced-over lake too slippery for operations. The sleet storm also ushered in a warming trend, however, and during the evening of8 January sentries noted that the radio aircraft seemed ready to break through the ice. All hands turned out to drag it to dry land. The group waited for better weather, and by the morning of 10 January the temperature had dropped enough to permit safe operations. The pursuits departed Selfridge at 0905 and arrived at Duluth, Minnesota, via St Ignace, Michigan, at 1520. The transports followed, arriving at Duluth by 1620. The observation aircraft, carrying H.J. Adamson, a representative of the Assistant Secretary of War for Air, developed engine trouble and stayed at Selfridge.

The group proceeded to Minot, North Dakota, on 11 January. That night, the temperature plunged to -20°F. After a starter ripped a frozen engine apart, the crews decided to wait for the transports to bring engine heaters. The transports arrived that afternoon, but one broke an axle on landing. On the morning of the 13th the pursuits took off for Great Falls, Montana. Leaking radiators caused delays, and the flight began to get strung out along the route. By nightfall on 13 January, the main body had reached Great Falls. One landed at Hosey, Montana, with a broken piston, and three spent the night at Havre after darkness prevented them from reaching Great Falls.

In the face of sub-zero temperatures and a howling blizzard, three pursuits and a transport reached Spokane on 17 January. Thirteen more arrived at about 1600 on 19 January. As his pilots, numbed with cold and exhausted, trickled in, the 1st Pursuit Group Commander, Major Ralph Royce, telegraphed Washington that "having battled forces of King Winter ten days and won from them secrets of how they intend to aid enemies of United States in wartime, the First Pursuit ... stands defiantly on the ice of Newman Lake, 15 miles east of Spokane ... and rests ... while battle wounds are healed." As of this point the detachment had lost only one pilot, hospitalized at Great Falls with an infected foot.

The aircraft took off for home on 23 January. The first leg took the crews from Spokane to Miles City, Montana, via Helena. The flight departed Miles City on schedule the next day, but poor visibility forced the aircraft to land on a farm owned by A.H. Arnold. The group lost an aircraft when one pilot crashed less than 100 yards from the Arnold home. It nearly lost a second when Major Royce plowed through three wire fences during his landing. The first six planes of the flight reached Bismarck on 25 January, with the rest arriving the next day. At the close of flying on the 26th, fifteen pursuits had reached Fargo. When the pursuits landed at Minneapolis the next day, Major Royce could at least account for all the planes with which he had left Selfridge. The radio plane was disabled in Minneapolis, but the other two transports were on hand and ready to continue the flight. The observation plane, late leaving Selfridge, followed the pursuits for a few days, then returned to Dayton. Seventeen pursuits stood at Minneapolis; Arnold kept watch on the wreckage of the eighteenth outside his front door. The pilot with the infected foot rejoined his comrades at Minneapolis; all personnel, less the observation crew, were on hand as well.

The eighteen fighters and two transports flew to Wausau, Wisconsin, on 28 January. The next day the pursuits flew from Wausau to Selfridge via Escanaba, Michigan, ending the Arctic Patrol Flight of 1930. The flight demonstrated that the Army had largely ignored the recommendations made after the Canadian flight in 1927. The pilots complained that their'flight suits remained excessively bulky and not warm enough. The Air Corps provided electric engine heaters, but the mechanics preferred to light "plumber's pots" under the aircraft to keep them warm. The little pots served the group well during the flight. The open fire blazing a few feet below the engine did not harm the aircraft.

The group stayed close to home after the return of the Arctic Patrol Flight. Training continued as the group prepared for the next maneuvers, scheduled for April at Mather Field, California. The group sent the equivalent of about two squadrons to the West Coast. Three groups of six pilots each departed Selfridge by rail in early to mid-March on the way to Seattle, Washington, where they picked up the group's first consignment of Boeing P-12Bs. These eighteen aircraft proceeded to Mather after the pilots completed their pre-acceptance checks. Group maintenance personnel began to deploy to Mather on 23 March 1930. The group launched twenty-two P-ls and two C-9s daily from 25 March through 27 March, but bad weather forced the flight to return to Selfridge each day. The P-ls, led by Major Royce, finally took to the air on 28 March and reached Mather via Chanute Field; Fort Crook, Nebraska; Cheyenne, Wyoming; Reno, Nevada; and Salt Lake City, Utah, on 2 April. The maneuvers lasted for about three weeks. On 28 April the group left Mather for Salt Lake City, Denver, and Cheyenne. A flight of eighteen P-12Bs and nineteen P-ls (the deployment cost the group three aircraft and one pilot) returned to Selfridge on 2 May 1930.

Eight days later, on 10 May, the group dispatched twenty-one P-ls to Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, to serve as defensive forces in a joint Air Corps/ Anti-Aircraft Service exercise. This force returned to Selfridge on 19 May ,just in time to bid farewell to nineteen P-ls of the 94th Pursuit Squadron that left on 23 May to participate in Joint Army-Navy exercises in the New York City area. They returned to Selfridge on 30 May.

The group devoted the summer of 1930 to the usual round of tactical training, demonstration flights, and airport dedications, but it soon faced a new challenge. On 2 October the Army activated the 36th Pursuit Squadron at Selfridge Field. The new squadron, destined to form part of the 8th Pursuit Group, was attached to the 1st Pursuit and staffed with a cadre drawn from each of the group's three squadrons and the group headquarters. The 36th eventually drew seven officers and 101 enlisted personnel from the 1st Pursuit. The 36th remained at Selfridge, attached to the 1st Pursuit Group, until mid-June 1932, when the Air Corps transferred the squadron to Langley Field. The War Department continued to use the 1st Pursuit Group as a depot of sorts: on 1 December it directed the group to send sixteen of its new P-12s to Mather for use by the 20th Pursuit Group.

Patterson Field, Ohio, hosted the 1931 maneuvers, and again the 1st Pursuit sent a large contingent. The 36th Pursuit Squadron, still attached to the group, apparently used its training time well: on 1 May 1931 the four squadrons held a "fly off' to determine which would serve as the group's demonstration unit during the maneuvers. The 36th won this competition handily. 53 The group deployed 85 pursuits and seven transports to Dayton on 15 May. After approximately three weeks of performing what were by now fairly standard maneuver operations - patrol, ground attack, and bomber escort and attack-the group returned to Selfridge on 7 June.

The on set of the Great Depression gave the 1st Pursuit several additional responsibilities. In 1931, the group participated in several air shows staged to benefit the unemployed. Group involvement ranged from two- and four-ship flights to squadron strength deployments to, for example, Indianapolis on 27 September 1931 and New York City on 16 October of the same year. Beginning in 1933, the group saw a handful of its officers detailed to work with the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal program designed to put unemployed youth to work on various conservation projects.

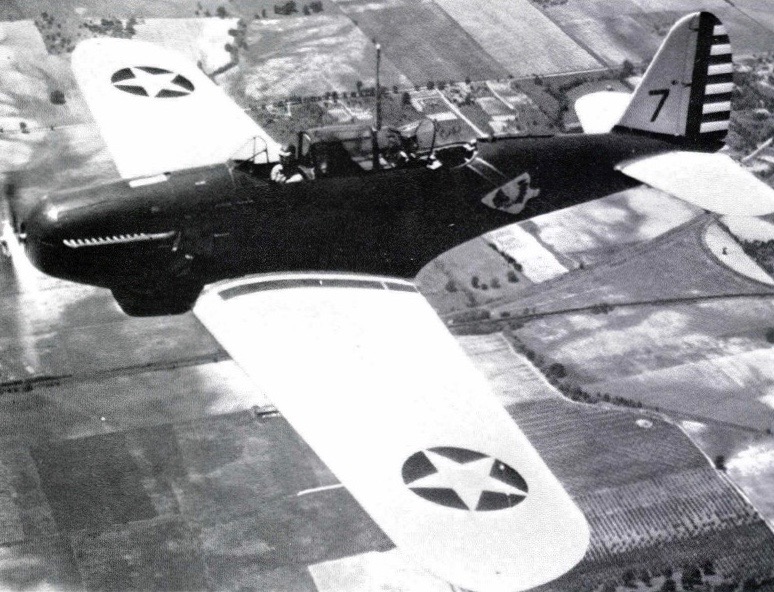

The most significant of the 1932 deployments saw a group strength movement of sixty-six aircraft (twenty-three P-6Es from the 17th; twenty-two P-12Es from the 27th; and twenty-one Y1P-16s from the 94th) to Chicago on 12 June for the George Washington Bicentennial Military Tournament. On the same day, the 1st Pursuit Group again became a three-squadron organization when the 36th Pursuit Squadron moved to Langley and the 8th Pursuit Group.

The group's yearly operational schedule included more than just a deployment or an occasional airshow. As during the Twenties, the more noteworthy events were part of a training program that still included periodic deployments to Oscoda, daily training flights in the Selfridge area, and occasional trips to various schools and arsenals to test new equipment or tactics. Airport openings still drew at least a small detachment. Equipment changes came more rapidly. As the list of aircraft deployed to Chicago in June 1932 showed, the group had discarded its P-ls in favor of a number of more advanced designs.

The P-6Es flown by the 17th were improved versions of the Curtiss Hawk line. Powered by a 600 hp Curtiss V-1570C engine, the Hawk had a top speed of 197 mph, a service ceiling of about 25,000 feet, and a range of 572 miles with its normal 100 gallon fuel load. The 27th flew Boeing P-12Cs, Ds, and Es. This design featured an all metal fuselage and a 600 hp Pratt & Whitney radial engine. The P-12 was somewhat slower than the P-6, with a top speed of 189 mph, but it had a higher service ceiling (26,300 feat). The range of the two types was similar: the P-12E's was 580 miles. 58

In 1932 the 94th Pursuit Squadron flew Berliner-Joyce Y1P-16s (later P-16s). While the P-16 was roughly the same size as the P-6s and P-12s, it carried a two-man crew, a pilot and a rear gunner. Equipped with a Curtiss V-157A engine, the P-16 had a top speed of 175 mph, a service ceiling of about 25,000 feet, and a range of 650 miles. The Army Air Corps procured only twenty-five of these planes, and it apparently assigned all of them to the 94th.

The pace of the group's training activities accelerated during 1933. On 6 January the Air Corps organized a Provisional Cold Weather Test Group at Selfridge, composed of five pursuits (P-6E, P-12C, D, E, and YlP-16, all from the 1st Pursuit) and two B-6As from the Langley-based 20th Bombardment Squadron. The group proceeded to Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan, for tests and a tactical exercise with the 2d Infantry on 14 February, then moved to Duluth for more tests on the 23d. The tests completed, the Provision Cold Weather Test Group disbanded on 15 March 1933.

The 1933 maneuver cycle consisted of an Air Corps anti-aircraft exercise in southern Ohio and Kentucky. The group began deploying maintenance and staff personnel on 20 April, and by the time the exercise began on 15 May the 1st Pursuit had fifty-nine aircraft available for service in the maneuver area. The 94th was based at Patterson Field, Ohio, and attached to the 3d Attack Group; the 17th and 27th were based at Bowman Field, Kentucky, and used by the defense. For the exercise, an infantry detachment, a signal unit, and the 325th Observation Squadron, Organized Reserve, augmented the group.

The 1933 exercise tested the antiaircraft net. The Bowman Field detachment spent most of the period from 15-24 May on alert, responding to aerial incursions tracked by a ground net and plotted by the group staff. The exercise also tested the applicability of radio to air defense. Some of the defending fighters carried radios, so the net spotted and tracked intruders and helped position interceptors for attacks. Bad weather grounded the pursuits for several days. When this happened, the group staff practiced tracking attack formations. From the air defense standpoint, the maneuvers were quite successful. During the final phase of the exercise the group completed eighteen of nineteen daylight interceptions, while the only night intercept attempted failed. The group returned to Selfridge on 25 May.

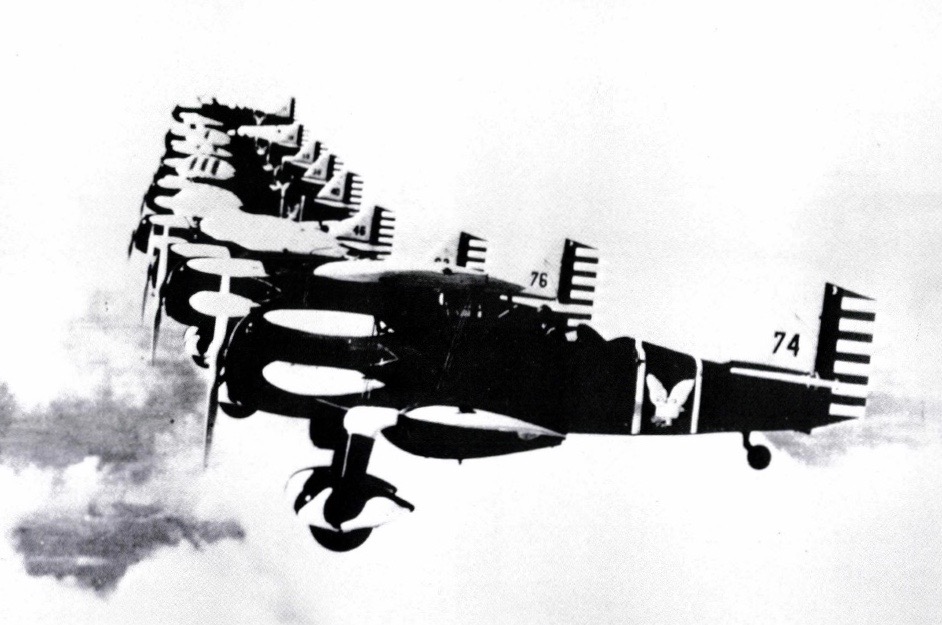

The 1933 World's Fair at Chicago kept the group busy throughout the summer. On 1 July a 72-plane formation led by the 1st Pursuit Group's commander, Major George H. Brett, performed an aerial demonstration in conjunction with the opening of the fair. On 15 July the group launched a 42-plane formation under the new group commander (as of 11 July), Lieutenant Colonel Frank M. Andrews, to escort the Italian Trans-Atlantic Flight of twenty-one Savoia-Marchetti S-55s under General Italo Balbo from Toledo to Chicago. On 18 July, the group again put seventy-two planes in the air for a demonstration over Chicago in honor of the Italians. The next day the group again launched seventy-two aircraft to participate in a farewell display for the Italians. The flight then escorted the Italian bombers eastward to Toledo before returning to base.

The 1st Pursuit Group had sixty-nine planes in service on 1 January 1934. These included one P-6A, one XP-6C, and sixteen Y1P-16s assigned to the 94th, and eleven miscellaneous cargo, observation, and training aircraft. 64 The year began with a scheduled series of winter deployments to Oscoda, but on 9 February the group received a message from Major General Benjamin D. Foulois, Chief of the Air Corps, advising it to be prepared to assign planes and pilots to air mail duty. Two days later President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the Air Corps to carry the mail while the administration resolved contract problems with commercial carriers.

War Department directives called for the 1st Pursuit Group to provide sixteen planes and thirty-five pilots for air mail duty, although the group eventually assigned about fifty pilots, including Lieutenant Curtis E. Le May of the 27th. Air Corps pilots in general were ill-equipped for the tasks they faced, and their equipment was not up to the test. The pilots had little training in night flying, the aircraft lacked adequate instruments, and ground facilities for cross-country flights were lacking. Bad weather compounded the problems. The result was a disaster. From 11 February to 23 June 1934, when the last officer from the group returned from air mail duty, group pilots were involved in ten crashes or forced landings that cost the Air Corps a similar number of aircraft. The group suffered two fatalities. On 22 February Lieutenant Durward 0. Lowry of the 94th became the first of twelve Air Corps pilots to die carrying the mail when his parachute became tangled in the tail surfaces of an 0-39 he was forced to abandon near Toledo, Ohio. The group's other fatality occurred on 26 April when Private First Class Donald Gagnier died in a motorcycle accident while performing air mail courier duty.

On 22 February, the same day Lieutenant Lowry died, another group pilot escaped with serious injuries when he flew his P-12E into the side of a mountain near Uniontown, Pennsylvania. The next day group pilots were involved in two crashes and two forced landings. All four aircraft, two 0-39s, a P-6E, and a YlP-16 were destroyed, but the only injury was a broken leg suffered when a pilot landed on a barn roof in Freemont, Ohio, after abandoning his aircraft. Lieutenant Newton Crumley, 27th, and Private First Class William G. LeTarte, 17th, probably suffered the greatest indignity on 2 April, when they were forced to jump from a burning B-6A near Winfield, Pennsylvania. Both landed safely, but they received cuts and bruises, and Private LeTarte suffered a broken leg, when the civilian "Good Samaritan" who picked them up after they landed lost control of his automobile and crashed down a mountainside while taking them to town.

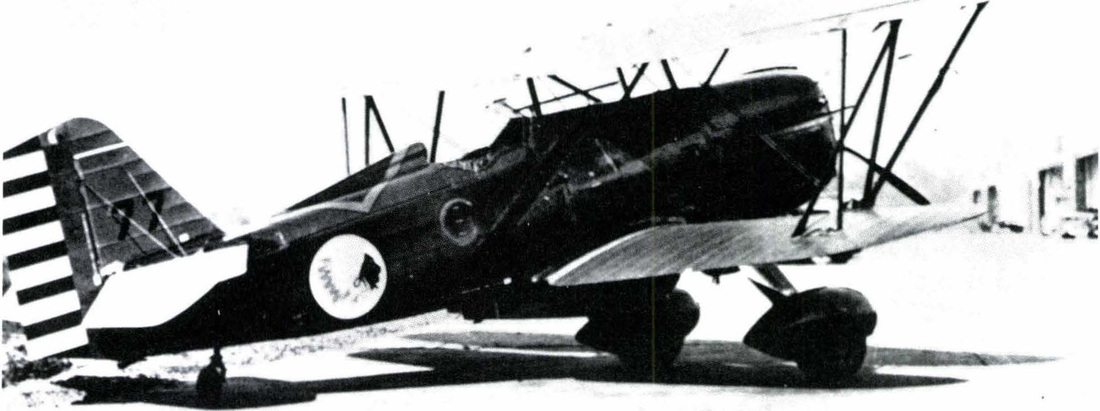

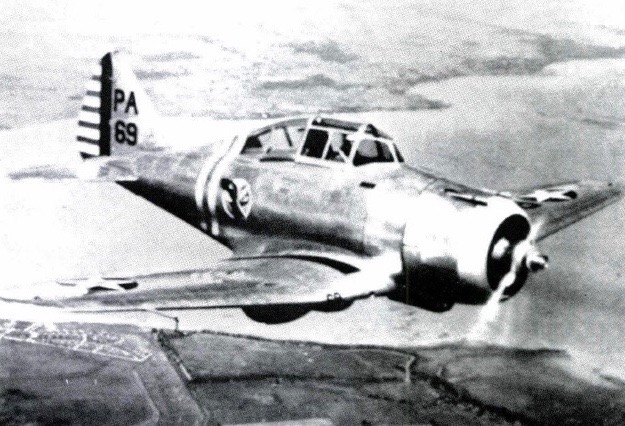

The group bid an undoubtedly fond farewell to the air-mail duty in June and resumed a more normal training schedule. It spent most of the rest of 1934 rotating crews through Oscoda, while the 17th Pursuit began converting to Boeing P-26As, a low-wing, all-metal monoplane, fitted initially with a 550 hp Pratt and Whitney R-1340-27 Wasp engine. The aircraft had a topspeed of about 235 mph, a service ceiling of 27 ,400 feet, and a range of 7 45 miles. Lieutenant LeMay ended a five-year tour with the 27th on 22 September 1934, when he was reassigned to the Hawaiian Department. On 10 October Lieutenant Colonel Andrews relinquished command of the group to Major Ralph Royce.

On 20 January 1935 another "Provisional Cold Weather Test Group" formed at Selfridge. By 1 February, when the group left Selfridge, it consisted of a collection of aircraft that included just about every model in the Air Corps' front-line inventory. The 1st Pursuit contributed three P-26As, three YP-12Ks, and the detachment commander, Major Ralph Royce. Three 0-43As from the 12th Observation Group were also assigned. A C-27A joined on 23 January, followed by two B-12As from the 7th Bombardment Group on 25 January. The 3d Attack Group contributed three A-12s, the last aircraft added before the group began its month-long cold-weather flight test.

Leaving Selfridge on 1 February, the group proceeded to its first stop, Alpena, Michigan, where it remained overnight. The group's itinerary over the next four weeks took it to Newberry and Hancock, Michigan; Duluth, Minnesota; Grand Forks and Minot, North Dakota; Great Falls, Helena, Miles City, and Billings, Montana; Bismarck, North Dakota; St Paul, Minnesota; Wausau, Wisconsin; and finally back to Selfridge Field on 27 February. The Air Corps officially disbanded the test group on 5 March. While several aircraft sustained varying degrees of damage due to rough landings and equipment failures, the test group suffered only one serious accident. On 7 February Lieutenant Daniel C. Doubleday of the 27th was severely injured when his P-26A spun in and was demolished on Portage Lake, Hancock, Michigan. The test group encountered the full range of winter weather conditions: a blizzard in northern Michigan, a thaw at Duluth, and dust storms and fog in Montana.

On 1 March 1935 the War Department established General Headquarters Air Force (GHQAF) at Langley Field, Virginia, "to command and control the Air Corps tactical organization." The headquarters, under Major General Frank M. Andrews, former 1st Pursuit Group commander, controlled three GHQAF Wings; on 1 March the 1st Pursuit Group was assigned to 2d Wing, GHQAF. On the same date the 38th Pursuit Squadron, attached to the 1st since its organization on 1 August 1933, was inactived, redesignated a long range amphibian observation squadron, and assigned to the 3d Wing, GHQAF. The 56th Service Squadron was activated and, with the 57th Service Squadron, assigned to 2d Wing, GHQAF and attached to the 1st Pursuit Group. The 17th, 27th, and 94th Pursuit Squadrons had their enlisted components slashed by two-thirds, from 132 to 43. Much of the rest of the month of March was spent reassigning personnel and adjusting to the new command structure.73 Between 17-19 May the group deployed to a camp established near Flint, Michigan, for a field test of the new GHQAF organization. A further mobility test was conducted from 5-10 June, when the 57th Service Squadron and the 27th Pursuit deployed on short notice to Kent County Airport, Grand Rapids, Michigan. The group completed both deployments without incident.

The pace of training accelerated in 1936. During February, the 17th and the 27th passed through the gunnery range at Barksdale Field, Louisiana. From 20 May through 5 June, the group conducted field exercises at its Oscoda range. The summer training cycle culminated in August, when the 27th deployed twenty-three PB-2As and the 94th twenty-eight P-26As to Chanute Field, Illinois, for Second Army maneuvers. This contingent deployed on 1 August. While en route, the flight intercepted bomber and attack formations moving to Illinois from Langley and Barksdale. The group returned to Selfridge the next day and operated from its home base for the remainder of the maneuvers, except for brief deployments to Bowman Field and Fort Knox, Kentucky, on 6-7 August. Two full-strength squadrons, one each from the 2d Bombardment and the 3d Attack Groups, also operated from Selfridge for the maneuvers, which lasted until 20 August.

Group support functions were reorganized on 1 September 1936. On that date the Group Headquarters and the 56th and 57th Service Squadrons were inactivated, consolidated, and redesignated Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, 1st Pursuit Group. At the same time the Station Complement, Selfridge Field, was redesignated Air Base Headquarters and Third Air Base Squadron.

A number of service organizations supported the 1st Pursuit Group since its activation in 1918. During World War I, Air Parks 1, 2, and 4 provided support. In late June 1921, Air Park No. 2 was redesignated the 57th Service Squadron and assigned to the 1st Pursuit Group. The 57th served with the 1st at Selfridge throughout the Twenties and Thirties, providing a maintenance and support echelon above the squadron level. Personnel transferred regularly between the 57th and the group's tactical components, and pilots assigned to the 57th flew the group's transports, which were also assigned to the service squadron. Each of the pursuit squadrons had, in addition to its complement of pilots, a maintenance component that consisted of a crew chief for each aircraft plus a number of specialists, including weapons specialists, airframe mechanics, and as the aircraft grew more complex, instrument and radio technicians. The 57th provided major maintenance support, including periodic overhauls and major structural repairs. The 57th also had sections devoted to supply, transportation, security and personnel.

The group hosted the twelfth running of the Mitchell Trophy race at Selfridge Field on 17 October 1936, the last of seventeen events conducted that day at the base to benefit Army Relief and the Mount Clemens Community Fund. The 1st Pursuit and several visiting formations kept the crowd, estimated at 40,000 people, entertained with a variety of aerial displays and races, including competitions for the Mount Clemens, Boeing, and Junior Birdmen trophies, the latter presented to the air reserve officer who won the "Junior Birdmen Speed Dash." Lieutenant John M. Sterling won the Mitchell Trophy for completing the five-lap, one hundred-mile race at an average speed of 217.546 mph.

The Air Corps organized yet another winter test detachment, this one called the "Cold Weather Equipment Test Group," at Selfridge in late January 1937. The 1st Pursuit contribution to the test group consisted of the 27th Pursuit Squadron, which flew to Oscoda on February 2d "to participate in intensive cold weather equipment tests.1179 A week later, on 9 February, the 27th returned to Selfridge but continued to participate in cold-weather tactical problems until 24 February, when the Air Corps disbanded the test group.

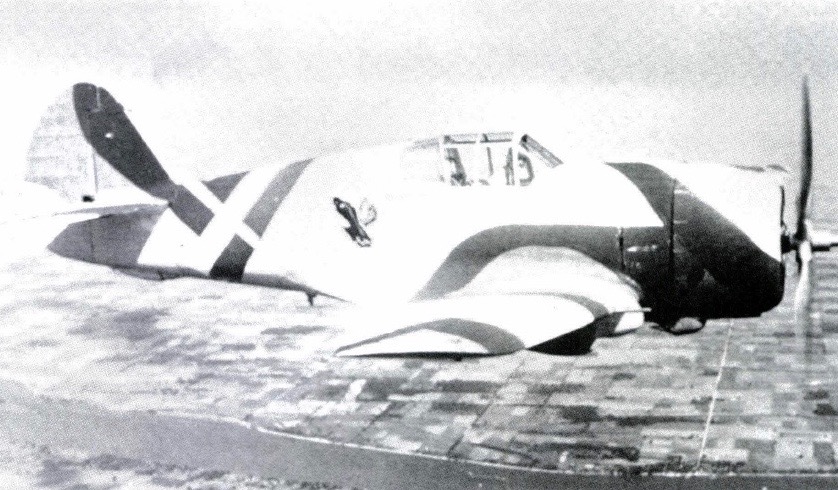

The 1st Pursuit Group brought a new generation of fighter aircraft into the inventory in 1937, when it took possession of its first P-35 and P-36 aircraft. Lieutenant Colonel Royce flew the first P-36 from the Curtiss plant at Buffalo, New York, to Selfridge on 7 April. While the group was still equipped with the metal and fabric, fixed-landing gear, open-cockpit Boeing P-26, the new designs featured retractable landing gear, all metal construction, and enclosed cockpits. The P-26's 600 hp engine gave it a top speed of about 235 mph. Powered by a 1,050 hp Twin Wasp, the P-35A had a top speed of about 305 mph. The Curtiss P-36 Hawk, powered by the same engine as the P-35, was capable of 313 mph at 10,000 feet. The P-36 Lieutenant Colonel Royce delivered was a test model, designated YlP-36. Following tests in May 1937 the Air Corps awarded Curtiss a contract for 210 Hawks - the largest Army fighter order since World War I. The new designs, which "displayed an aesthetic elegance as they flashed through the sky," served the group as a bridge between the P-26 and the aircraft it would fly in World War Il.

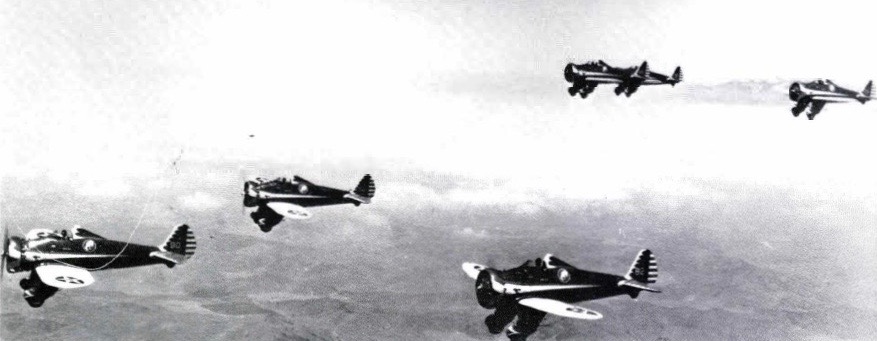

Although the group was converting to more modern aircraft, it still took its P-26 and PB-2s to Muroc Dry Lake, California, for the 1937 Air Corps maneuvers. On 1 May sixteen transports, carrying a 168-man advance party, left Selfridge. This party arrived at Muroc the next day as the 27th, with fifteen PB-2As, and the 94th, with twenty-eight P-26Cs, left for California. On 3 May the 55th Pursuit Squadron, twenty-eight P-26As from Barksdale, arrived and was attached to the 1st Pursuit. More aircraft arrived at Muroc on 4 May, when the 27th was brought to full strength with the attachment of eighteen PB-2As from the 8th Pursuit Group. (The squadron's full strength was twenty-eight aircraft; five of the aircraft that flew out with the 27th belonged to the headquarters detachment.) Transports brought additional enlisted detachments from Selfridge on 6 and 10 May. At 0800 on 10 May the full-strength 1st Pursuit Group - 27th and 94th assigned, 55th attached - went on alert as the maneuvers began.

This exercise pitted the group's fighters against bombers and attack aircraft in antiaircraft tests, a scenario much like the one used in 1933 in southern Ohio. The group staff plotted intruders and vectored on-station pursuits to intercept them. Operations on 11 May were typical. At 0300 the group command post learned of bombers approaching the patrol area. The 27th scrambled at 0313; the 55th followed at 0322; the 94th remained in reserve. A formation of eighteen attack planes entered the air defense zone at 0327. The 27th attacked the intruders at 0341 and 0351. The 94th scrambled at 0400, just before the attackers gassed the airfield at Muroc with real tear gas and simulated mustard gas. Elements of the 27th intercepted a bomber formation at 0427. Another formation from the same squadron met the bombers at 0437, while a third group faced still more attackers at 0447. The 27th picked up yet another attacking group over Muroc at 0459. The fighters landed at dispersed airfields at 0525. The three squadrons scrambled again at 1430, and the 55th made its first interception five minutes later. The 55th picked up more attackers at 1440, 1455, 1515, and 1522. The 27th made its attacks at 1450, 1504, and again at 1518. The group landed at 1550. The next day's battle began at 0320. The group maintained this schedule for twelve days, through 21 May, although the schedule usually called for only one sortie per day. A tired 1st Pursuit Group returned to Selfridge on 26 May.

The group followed a similar schedule for the rest of the decade. In 1939 its P-36s, especially those of the 27th, sported experimental camouflage schemes that included such bizarre combinations as green, yellow, orange and white; lavender, "bottle green," olive drab, orange and white; forest green, lavender, orange and white; and gray, lavender, olive drab, and forest green.

On 23 October 1940 the 17th Pursuit Squadron was relieved from assignment to the 1st Pursuit Group and transferred to the Philippine Department. Leaving Selfridge on 31 October, the squadron served in the defense of the Philippines until the spring of 1942 when the remnants of the squadron, fighting as infantry, were destroyed at Bataan. The War Department carried the squadron as an active unit, but it was not operational from the fall of the Philippines until 2 April 1946, when it was deactivated.

The group was short a squadron, but not for long. On 1 January 1941 the 71st Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor) was activated at Selfridge Field and assigned to the 1st Pursuit Group (Interceptor) - a redesignation effective 6 December 1939. Despite folklore to the contrary, there is no evidence that the War Department chose the new squadron's designation by reversing the old squadron's number. The 94th provided the 71st's cadre, and the new squadron began training immediately. In the summer of 1941 it joined the group at the 1941 GHQ maneuvers in Louisiana and South Carolina.

In July 1941 the 27th received the first models of the aircraft the 1st would take to war. The Lockheed P-38 Lightning "represented one of the most radical departures from tradition in American fighter development. 1188 The Lightning featured a wing span of 52 feet and was 37 feet 10 inches long. The P-26C the 94th took to Muroc in 1937 had a span of 28 feet and a length of 24 feet. The Lightning's two turbo-supercharged Allison V-1710s each produced 1,475 hp, giving the plane a top speed of 414 mph at 25,000 feet. The P-26, powered by a single 660 hp engine, attained a top speed of 234 mph at 7,500 feet. The Lightning carried four .50 caliber machine guns plus a 20mm cannon, the P-26 two .30 caliber or one .30 caliber and one .50 caliber machine guns.

On 5 December 1941, Captain Ralph Garman led the air echelon of the 94th, consisting of twenty P-38s, to March Field, California, for what was to be a ninety-day temporary duty assignment. The 94th was at El Paso, Texas, when it heard about Pearl Harbor.

The group's initial tour in Michigan lasted less than ten days. On 28 August the four squadrons departed by train for Kelly Field, Texas. The newly organized group headquarters, under the command of Captain Arthur E. Brooks, left Selfridge for Kelly two days later. For the next three years the group remained in Texas, where it operated the Advanced Pursuit Training School.

The leaders of the Army Air Service knew that the organizational and operational lessons learned during World War I would shape postwar activities, but in the haste to demobilize after the war the Army broke up units without giving adequate thought to its future needs. As the organizational situation stabilized at the end of the summer of 1919, the Army began to devise better considered defense plans, and it also recognized that the proper application of the lessons of the war required a carefully planned training program. The decision to use the 1st Pursuit Group as an Advanced Pursuit Training School" reflected this thinking.

The Army used the pursuit school to build an effective fighter force in stages, beginning with the fundamentals of flying and culminating in group-strength fighter maneuvers. The course of instruction for pilots at Kelly consisted of a twenty-week program of classroom and in-flight training. Topics covered included squadron, group, and air service history, the history of aircraft and aero-engine design, development, and maintenance, aeronautical theory, military and aerial strategy and tactics, weather, navigation, operational procedures, and organizational theory and practices. Pilots received hands-on experience in aircraft and engine maintenance. They also flew a 72-hour program that covered formation flying, aerobatics, air-to-air and air-to-ground gunnery, reconnaissance and patrol tactics, and emergency procedures. In addition, pilots served liaison tours with bombardment and attack units and with infantry, cavalry, armor, and artillery formations to improve intraservice understanding and coordination. Pilots also made a number of tethered and free lighter-than-air flights.

After completing this part of the syllabus, the pilots joined a squadron, where their training entered another stage. They spent somewhat less time in the classroom, more in the air. When the pilots learned to fly and fight as part of a larger unit, training progressed to the group level. This phase of the course included some group-strength formation flights and squadron-versus-squadronair combat, but the pilots again returned to the classroom for work in the fundamentals of officership, command, management, and staff activities. While the Advanced Pursuit Training School trained the pilots, the group's mechanics and support personnel kept busy with their own course of classroom and field work. They practiced their trade by working on aircraft used to support the flight training syllabus.

The 1st Pursuit Group's work at the Advanced Pursuit Training School, initially at Kelly and later at Ellington Field, Texas, established a solid foundation that the group built on during the next decade. During the 1920s the group was the Army Air Corps' only group-level pursuit organization. As such, the Army repeatedly called on it to evaluate new aircraft designs, test equipment under a variety of operating conditions, demonstrate aircraft and unit capabilities, and practice advanced tactics during Air Corps and Army maneuvers. The group also flew numerous public relations flights throughout the eastern and mid-western United States. The years in Texas forged the group into a competent, cohesive unit. The group used this training as the basis for more demanding projects undertaken during the Twenties.

The 1st Pursuit Group prepared to return to Michigan in late June 1922. It still consisted of four squadrons, although the 14 7th had been redesignated the 17th Aero Squadron on 3 March 1921. The air echelon, consisting of the 17th, 27th, 94th and 95th squadrons and led by the group's commander, Major Carl Spatz (later Spaatz) departed Ellington Field on 24 June 1922. The ground component followed on 27 and 28 June. The long aerial deployment was a novelty, and the public and the press followed the group's progress closely. The aircraft arrived at Selfridge Field on 1 July 1922.

Selfridge served as the group's home for many years. The field was situated on i:t 641-acre site located northeast of the city of Mount Clemens, a suburb of Detroit. It was named after Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge, one of the Army's first pilots, who died in the crash of a Wright Flyer flown by Orville Wright on 17 September 1908. The site was reclaimed swampland, and poor drainage plagued the field for years. Nonetheless, the group settled into its new home and began preparations for an event that became a hallmark of the 1st Pursuit.7 The National Air Races took place at Selfridge Field from 7-14 October 1922. Included in the program was the first running of the Mitchell Trophy Race. Brigadier General William Mitchell donated the John L. Mitchell Trophy to the Air Service in memory of his brother, lost in action during World War I while serving with the 1st Pursuit Group. Mitchell aimed to stimulate the development of better pursuit aircraft, and the races, held from 1922-1930 and from 1934-1936, became a key proving ground for new pursuit designs. The first Mitchell Trophy Race seems to have been open to all qualified entrants, but the entry criteria soon became more restrictive. To be eligible for the Mitchell Race, a pilot had to be a Regular Army officer and a member of the 1st Pursuit Group who had served at Selfridge for at least one year and had accumulated at least 1,000 total flying hours. A final qualification made the race especially significant for the group's pilots: a pilot could fly in only one Mitchell Trophy Race. Lieutenant Donald F. Stace of the 27th won the first Mitchell race. He made four circuits of the twenty-mile course in his Thomas-Morse MB-3 at an average speed of 148.1 mph.

The Mitchell Trophy Race provided a moment 9f excitement each year, but most of the group's regular operational activities throughout the decade were far less glamorous. As the Air Corps' only pursuit group, the War Department took special pains to ensure that the 1st maintained a high state of readiness. It conducted quarterly inspections and mobilization tests during 1923, 1924, and 1925. The units performed well during these tests, but to maintain its edge the group itself conducted its own regular inspections and practice alerts. These types of activities have long dominated the peacetime operating schedule of all types of military organizations; the interwar 1st Pursuit Group was no exception.

In 1924 the War Department sanctioned unit emblems. On 21 January 1924, the Adjutant General approved the emblem of the 1st Pursuit Group. The design of the device reflected the unit's history. The colors of the shield, green and black, represented the original Army Air Service. The five stripes stood for the group's five original squadrons, and the five crosses symbolized the group's five major World War I campaigns: Champagne-Marne, Aisne-Marne, St Mihiel, Verdun, and Meuse-Argonne. The colors of the crest, with its golden winged arrow on a sky-blue disc, were the colors of the Army Air Corps. The crest bore the group's motto: "Aut Vincere Aut Mori" - "Conquer or Die." Revisions made in 1957 deleted the crest and added the scroll at the base of the shield.

The Adjutant General also approved unit emblems for the squadrons. The "Great Snow Owl," white on a black background, became the official emblem of the 17th Pursuit Squadron on 4 March 1924. The next day the World War I-vintage "Kicking Mule" emblem was officially assigned to the 95th Pursuit. On the same day, 4 March, the 27th's "Diving Eagle" became a "Diving Falcon," because the War Department did not want to appear to be endorsing a brand of beer.

Commercial considerations forced the War Department to change the emblem of the 94th. During the early 1920s Eddie Rickenbacker decided to produce a line of automobiles that bore his name. Rickenbacker adopted, as the company's logo, the hat-in-the-ring device the 94th had used as a unit emblem during the war. Again in an effort to avoid appearances that it was promoting a product, the Adjutant General's office decided, on 6 September 1924, that the 94th would use the Indian-head device formerly used by the 103rd Aero Squadron, a World War I unit formed when the members of the Lafayette Escadrille transferred to the Army Air Service after the United States entered the war. Even though the Rickenbacker was not a commercial success and the company soon went out of business, the 94th continued to use the Indian-head insignia until 1942.12

The group also opened a satellite facility in 1924. On 18 May thirty enlisted men left Selfridge for Oscoda, Michigan, to establish an "Aerial Gunnery Camp" for the 1st Pursuit Group. Facilities at the camp were spartan at first, but during the course of the next decade the group made numerous improvements at the site. Such improvements were necessary, because the squadrons of the 1st Pursuit returned to Oscoda regularly for gunnery practice against towed and ground targets. These deployments usually included one of at least squadron strength during January or February, intended to test aircraft in severe winter conditions, and a larger deployment during the spring devoted to gunnery practice. The group also regularly rotated squadrons through Oscoda to prepare them for special tests or maneuvers.

Beginning in about 1925, the group participated in exercises, demonstrations, and maneuvers, events the War Department used as combined training and public relations exercises. Public and congressional interest in aviation was high. The group flew fast, nimble, pursuit planes that attracted the attention of earth-bound taxpayers wherever they appeared. At the same time, the War Department wanted to test evolving doctrines and tactics that would enable the air arm, especially tactical aviation, to work effectively with other branches. As a result, the group's Selfridge training schedule often aimed to prepare the unit for demanding summer and fall activities.

The 1925 training cycle was typical. Between May and October the group completed four formal tactical inspections and participated in a mobilization test on 4 July that saw it dispatch planes to Alpena, Oscoda, and Frankfort, Michigan, Washington, DC, and Youngstown, Ohio. On 26 February, group commander Major Thomas G. Lanphier led a flight of twelve PW-8 aircraft from Selfridge to Miami, Florida, in an attempt to set a dawn-to-dusk flight record. The flight reached Macon, Georgia, by mid-afternoon, when bad weather forced the planes to the ground. The aircraft finally reached Miami on 2 March. The War Department made use of the contingent's presence on the East Coast to put on a demonstration for Congress and the press.

The demonstration was held at Langley Field, Virginia, on 6 March. A static display on the flightline enabled the assembled congressmen to examine the planes. The aerial portion of the demonstration, which occupied most of the afternoon, used as its scenario a simulated attack on a battleship silhouette. The 1st Pursuit's twelve aircraft opened the attack by strafing the silhouette and dropping light bombs. The fighters then laid a smoke screen to cover the attack of heavy bombers and attack aircraft, which the fighters protected and attacked in turn.

The spectators seemed duly impressed with this demonstration, but some contact with members of Congress brought the group rather less favorable attention. On 26 March 1925 Lieutenant Russell Minty's aircraft failed to clear a stand of trees and crashed shortly after takeoff from an airfield near Uniontown, Pennsylvania. The pilot escaped injury but his passenger, a Pennsylvania congressman, was not so lucky. He was badly cut and bruised and suffered a broken collarbone and several broken ribs. The congressman's reaction to this mishap is not recorded, but the group diary noted Minty's transfer to non-flying duties on 27 March.

The unfortunate Lieutenant Minty had a bad year in 1925. Returned to flying status, he joined five other 1st Pursuit Group pilots detailed to fly from San Francisco to New York to test a new transcontinental air-mail route. The group left Selfridge on 15 July. On 31 July Minty escaped injury when his P-1 crashed and sank in the Des Moines River during a night flight from Cheyenne, Wyoming, to Chicago. The circumstances of the lieutenant's mishap served as an unfortunate precursor of the group's later involvement with carrying air mail.

An inspection conducted by Major General Mason M. Patrick, Chief of the Air Service, on 29 January 1926 ushered in another busy year for the 1st Pursuit Group. After winter maneuvers at Oscoda, the group deployed a detachment of eighteen aircraft (eight PW-8s, seven P-ls, two P-lAs, and one C-1) to Wilbur Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, on 19 April to participate in Army Air Service maneuvers. The purpose of this exercise was "to train the Air Brigade Staff and the lesser Staffs in the technique of air force units during concentration of ground forces up to a point just before the actual meeting of the ground forces." It was the second of three such exercises: the first, in 1925, simulated an attack on the coast and focused on the staff work required to concentrate aircraft at the point of attack; the 1927 exercise simulated air operations during the land battle. The 1926 maneuvers began with a command post exercise. The flying units based subsequent tactical operations on situations that had developed during the first phase.

In addition to the 1st Pursuit's seventeen aircraft, the Army Air Service detachment at the maneuvers included thirteen aircraft from the 2d Bombardment Group and twelve planes from the 3d Attack Group. Two aircraft formed a "Provisional Observation Group." The main tactical problems covered during the operations phase included pursuit patrols versus bomber and attack aircraft, with special emphasis on the development of pursuit tactics against both types. The group also worked on offensive tactics, including rendezvous, attack formations, and escort tactics. During seven days of flying the 1st Pursuit Group flew 154 sorties and 186 hours. In his report on the maneuvers, Brigadier General James E. Fechet, Air Service Chief of Staff, expressed concern that pursuit tactics, which he feared were becoming too inflexible, exposed the pursuit planes to defensive fire for too long. The maneuvers also pointed out that the units needed more practice in long-range formation flying.

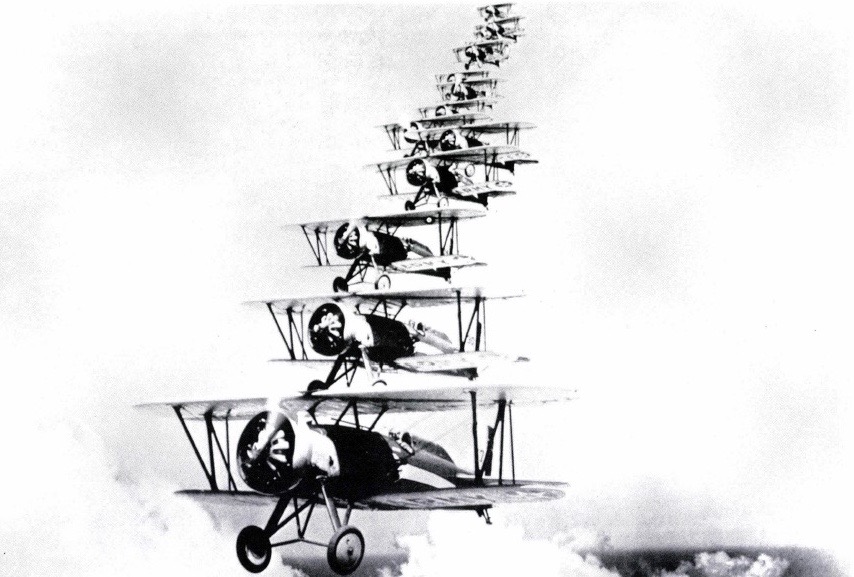

The maneuvers detachment returned to Selfridge on 1 May 1926. Later that month, the group sent three P-ls, three pilots, and twenty mechanics to Camp Anthony Wayne, Pennsylvania, where they served as part of the Air Corps (the Air Service became the Air Corps on 2 July 1926) Demonstration Detachment at the Declaration oflndependence Sesquicentennial Exhibition at Philadelphia. The other members of the group continued to carry on training at Oscoda and Selfridge throughout the summer. On 26 September six pilots flew their P-ls to Kelly Field, Texas, for temporary duty in support of the filming of the movie Wings.

The group's activities peaked in 1927 and 1928. Increasing interest in the effects of cold weather on operations took twelve aircraft to Canada from 24-30 January 1927. The army wanted to "determine the limitations of aircraft and equipment when operating under deployed conditions in a severe climate" and to test various types of skis for use on aircraft. The Canadian government welcomed the test contingent as a good-will gesture, and the War Department approved the flight on 23 January. The group deployed thirteen aircraft (six P-lAs, four P-lBs, two P-ls, and one Douglas C-1 transport), thirteen pilots and six mechanics from Selfridge to Ottawa the next day.

Conditions in Canada proved ideal for the test. The aircraft arrived in the midst of a blinding snowstorm, and "the poor visibility and the difficulty of keeping the landing area clear of pedestrians somewhat hindered the Flight in landing." The landing area on the Ottawa River was covered with twenty inches of snow, and the aircraft's rear skids broke through the crust, causing damage to each of the aircraft. Canadian mechanics helped install large disks on the tail skid to support the aircraft.

Temperatures got no lower than 20°F during the night of 24-25 January, but this was enough to chill the engines thoroughly. Mechanics filled them with hot oil the next morning, but they were still too cold to start. "Hot bricks placed in the air intakes close to the carburetor, used to vaporize the ether priming" did not work well either.

The mechanics finally borrowed a fire hydrant defroster from the Ottawa Fire Department, forced steam into the engines, and got them started. The detachment commander noted with interest, however, that the P-lBs equipped with self-starters turned over much more readily on the cold morning.

The Canadian flight's luck with the weather continued. The aircraft departed Ottawa in the early afternoon of 25 January. They ran into another blinding snowstorm, landed on the Ottawa River, took off when the storm cleared, landed when another squall developed, then took off a third time. The 100-mile flight took about two hours, and the section finally arrived at Montreal. Mechanics drained the water and oil from the engines, but that still left the pursuits poorly prepared for the -20°F they faced the night of 25-26 January. Three-man crews, working ninety minutes on each aircraft, got all planes started the next morning.

Flying on the 26th was uneventful, but the thermometer dropped to -22°F that evening. The crews delayed the takeoff of their flight to Buffalo, New York, because "it was doubtful whether it would have been possible for the pilots to have withstood the cold for four hours in their present type of flying equipment.1125 By about 1300 eleven of the twelve pursuits were ready to depart, but a sticking carburetor prevented the twelfth from starting. Nine aircraft took off about 1400, but a storm forced them down near Fisher's Landing, New York. The aircraft "taxied to a position in the shelter of the boat house and wharves on the shore of the little cove." The storm did not abate, so the pilots stayed in Fisher's Landing overnight. The nine-plane flight reached Buffalo on 29 January.

In the meantime, the three aircraft left behind in Montreal took off at about 1530 on 28January, but poor visibility forced them to turn back. They took off again at about 1100 the next day and reached Alexandria Bay, New York, before a radiator leak in one plane forced the flight down. The three took off and reached Woodville, New York, when one aircraft's broken oil line forced them down again. Two continued while the pilot of the damaged aircraft repaired the oil line. The two-plane flight landed near Irondequoit Bay when a radiator overheated. On takeoff the plane that suffered the radiator leak lost its engine. The three planes finally staggered into Selfridge between 30 January and 1 February. The nine planes from Buffalo arrived at Selfridge on 30January.

The flight commander's recommendations came as no shock to those who followed the flight's progress. The Air Corps needed aircraft with engine block heaters and self-starters, a stronger tail skid for its aircraft, and a warmer and more comfortable winter flying suit.

The 1927 maneuver/demonstration cycle began on 27 April, when Captain Hugh M. Elmendorf, commander of the 94th, led a five-plane flight from Selfridge to Bolling Field, DC. The flight then proceeded to Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland, where mechanics added smoke generators and the pilots learned how to lay the smoke in conjunction with armor and infantry attacks. This flight then made its way to Pope Field, North Carolina; Atlanta, Georgia; Fort Benning, Georgia (where it put on tactical demonstrations for the instructors and class at the Infantry School); Mansfield, Louisiana; Galveston, Texas; and finally Kelly Field, Texas, where the Army held its 1927 maneuvers.

A second demonstration flight of eight P-ls, led by Captain Frank H. Pritchard, left Selfridge on 3 May. This group flew demonstration flights at Fort Riley, Kansas, and Fort Sill, Oklahoma, before arriving at Kelly Field on 10 May. The next day the group launched eighteen more P-ls for Kelly, this detachment led by Major Thomas G. Lanphier, the group commander. The detaehment left Selfridge at 0630. It arrived at Kelly at 1815 after making two intermediate stops, where waiting group mechanics serviced the aircraft. When the maneuvers began on 15 May, the 1st Pursuit Group had thirty-one P-ls deployed at Kelly Field, with thirty-one pilots, twenty-one mechanics, and twelve support specialists.