World War I

On 15 January 1918, a small party 6f Americans arrived at the French village of Villeneuve-les-Vertus, located about ten miles south of Epernay. Ordered from Paris two days before, the little band, led by Major Bert M. Atkinson and composed of Captains Philip J . Roosevelt and John G. Rankin, six sergeants, and a civilian, formed the vanguard of the people and organizations that would, five months later, form the 1st Pursuit Group. Major Atkinson, fresh from meetings with Brigadier General Benjamin D. Foulois, Chief of the Air Service, American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), and Colonel William Mitchell, Air Commander, Zone of Advance, knew that the American people expected much from the Air Service. He also knew that the air arm could claim no real accomplishments to that point, even though America had been at war for more than nine months. Foulois and Mitchell therefore told Atkinson and his staff "to get started as quickly as possible.

Major Atkinson wasted little time in organizing a staff for the "1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center" established at Villeneuve-les-Vertus on 16 January 1918. He appointed Captain Roosevelt adjutant and Captain Rankin supply officer, and they set to work. Despite their good intentions, the conditions Atkinson, Roosevelt, and Rankin encountered in France complicated their work. The American staff in Paris had assured them that Villeneuve-les-Vertus was a spacious, well-equipped airfield ready to receive the three pursuit squadrons then completing the training course at the advanced training school at Issoudun, where American pilots transitioned from the trainers they flew in the United States to the high performance fighters they would fly at the front. Combat-ready Spads supposedly sat at French factories, awaiting the arrival of the pilots from Issoudun to ferry them to the front. The Americans found, to their chagrin, that the staff in Paris had little grasp of the actual situation at the front.

Villeneuve proved to be a first-rate airfield, but the French 12th Groupe de Combat occupied all its facilities. The squadrons training at Issoudun were far from being ready for combat at the front. As for the Spads, the French suggested that they might be able to supply some in six months or so, but French aviation officers reported that they had few they could spare at the time.

Captain Rankin, the supply officer, sized up the situation. He used some of his funds to purchase a quantity of champagne, and with its help and a little innovative bargaining, he obtained shop space from the French unit at Villeneuve-les-Vertus. By the middle of February, about a month after their arrival, Major Atkinson and his growing Training Center staff had managed to build or borrow a barracks and hangar space for thirty-six aircraft. When Atkinson reported that these limited facilities were available, the American staff in Paris dispatched to the airdrome the squadrons that would soon make up the 1st Pursuit Group. The 95th Aero Squadron reported on18 February 1918. The 94th Aero Squadron rolled into camp two weeks later, on 4 March. Neither squadron possessed any aircraft, but Major Atkinson and Captain James E. Miller commander of the 95th, began pursuing some promising leads.

The 94th and 95th Aero Squadrons had trained and travelled together since their organization on 20 August 1917, at Kelly Field, Texas. First Lieutenant J. Bayard H. Smith became the first commander of the 94th, while First Lieutenant Fred Natcher led the 95th. When the two squadrons boarded a train at Kelly Field on I - 20 September 1917 for the trip to Mineola, New York, they consisted entirely of the enlisted echelon that would form the squadron's ground support element. Arriving at Mineola on 5 October, the squadrons reported directly to Aviation Mobilization Camp No. 2. Each unit completed training there in about three weeks and proceeded to Hoboken, New Jersey, where, on 27 October 1917, they boarded a ship for the trip to Europe. The two squadrons arrived at Liverpool on 10 November, spent fourteen hours in a rest camp, boarded a steamer at Southampton, and sailed for France on 12 November. The 94th and 95th entered camp at LeHavre the next day, but their travels were not quite over. On 15 November the 95th moved to the Aviation Training Center at Issoudun. On 18 November the 94th moved to Paris, where it divided into seven detachments that immediately began advanced maintenance training in the region's airframe and aero-engine plants. The 94th reassembled in Paris and departed for Issoudun on 24 January 1918.

After the 95th's personnel arrived at Issoudun in November, they received advanced training on the same types of aircraft they would operate at the front. The 95th thus found itself well along in its training when the 1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center announced its readiness to receive units in mid-February, and it became the first unit to be attached to the center. The 94th made good progress at Issoudun, however, and it reported to Villeneuve not long after the 95th. Captain Miller remained in command of the 95th when it arrived at Villeneuve; Major John F. Huffer commanded the 94th.

The 1st Pursuit Center controlled a pair of combat units, but neither was ready for combat. The newly-assigned pilots and maintenance personnel were eager, but they had little with which to work. Major Atkinson had obtained only a handful of

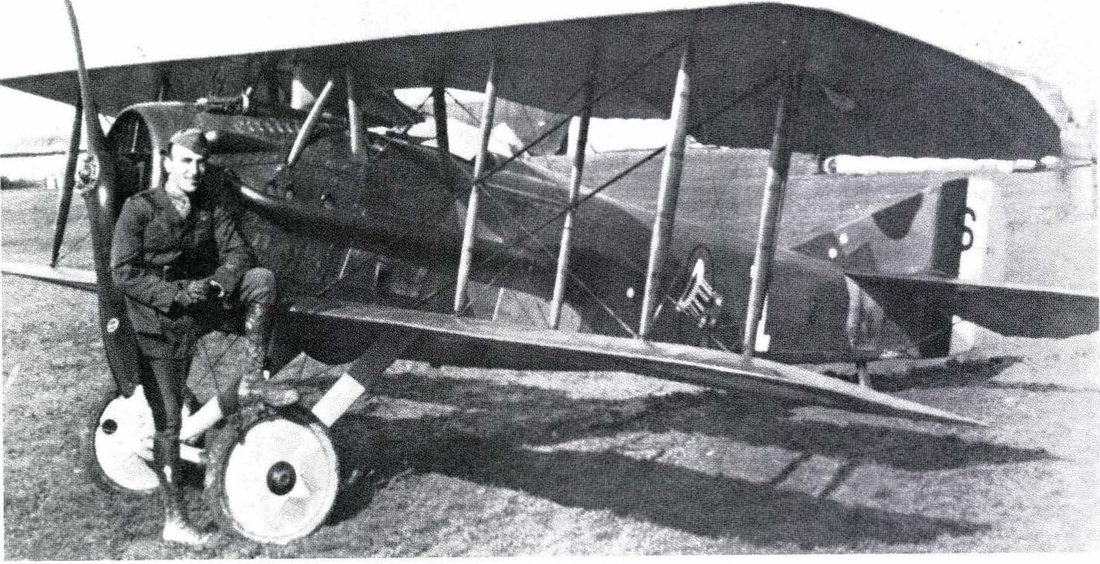

aircraft from the French, all Nieuport 28s, France's second-line fighter. The French reported that they had no surplus Spads available to equip the Americans, so Atkinson and his staff agreed that the units would see action sooner if the Americans accepted the more readily available Nieuport. On 26 February they received word that thirty-six Nieuports were waiting to be picked up at a factory near Paris. A contingent of pilots departed within hours, but bad weather delayed their return. The weather broke on 5 March, allowing fifteen pilots to take off for Villeneuve. Only six successfully completed the return flight that day. Weather and mechanical difficulties forced the others to land along the route. All the Nieuports reached Villeneuve by 8 March, and Atkinson assigned most of them to the 95th.

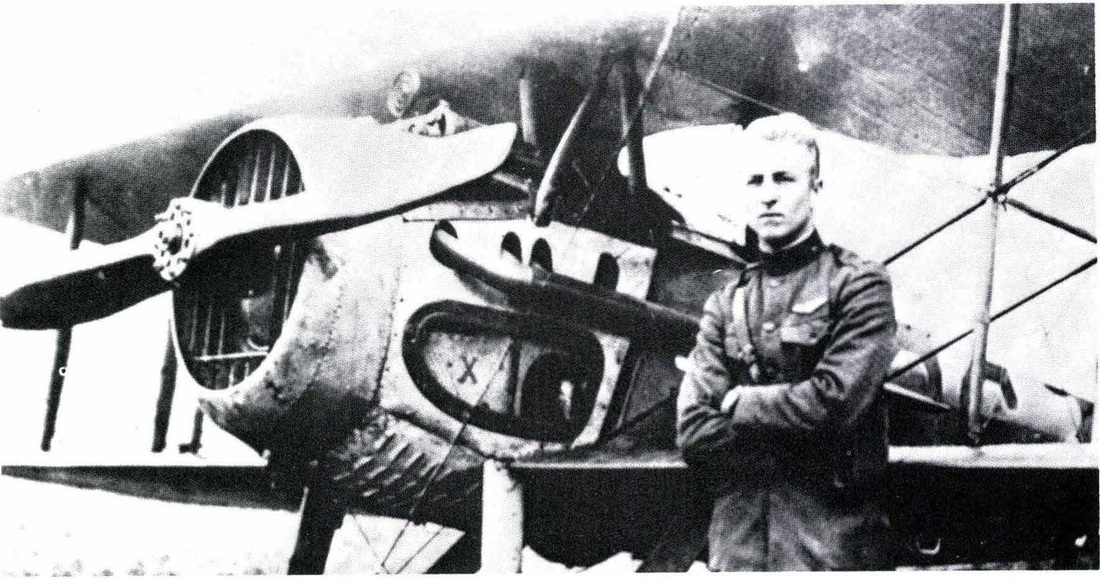

Even as the 95th lay claim to the first sizable contingent of aircraft, the 94th made its bid for fame by launching, on 6 March 1918, the first patrol flown by an all-American squadron in France. At 0815, Major Raoul Lufbery led two young first lieutenants, Douglas Campbell and Edward V. Rickenbacker, on a two-hour patrol near Rheims. A German antiaircraft battery challenged the flight, but it encountered no aerial opposition, a fortunate circumstance, since neither Campbell's nor Rickenbacker's aircraft carried any armament. The two neophytes believed they had flown an uneventful patrol. To their surprise, the more experienced Lufbery calmly pointed out that he had spotted no less than ten Spads, four German fighters, and a German two-seat observation aircraft during the patrol. He also showed Rickenbacker holes in the fabric skin of the younger pilot's aircraft, a reminder of their brush with the German battery.

The 95th made its first flights on 8 March 1918. These missions followed the pattern the 94th established during its first sorties. An experienced pilot, frequently either Major Lufbery or someone from the French group, led two or three Americans on a patrol over a quiet sector of the front. The Americans made great sport of these unarmed patrols, but the French expressed more concern. The initial patrols proved uneventful, but they were not without their risks. The frail Nieuports had several mechanical and structural faults, and engine trouble in a Nieuport contributed to the 1st Pursuit Center's first combat loss.

Captain Miller, commander of the 95th, experienced engine trouble on a training flight on 8 March 1918. He landed safely at Coincy and returned to Villeneuve by truck. On 10 March he returned to Coincy to pick up his aircraft. On the way back to the Center, Miller stopped to visit some friends at the airfield at Coligny, where he borrowed a Spad and flew a patrol over Rheims in the company of two other pilots. German fighters attacked the flight; Miller died in the ensuing dogfight. Captain Seth Low assumed command of the 95th, but Major Davenport Johnson, who flew with Miller on his final flight, replaced Low on 15 March.

As training operations continued and the pilots gained proficiency, morale in both squadrons soared. The A11ies anticipated a German offensive on the Western Front, and the members of the two squadrons sensed that their real baptism of fire was at hand. With this prospect in mind, the members of the 94th began to discuss the design of a unit emblem. The 94th's commander, Major Huffer, suggested that the squadron use Uncle Sam's stovepipe hat. Lieutenant Paul Walters, squadron medical officer, suggested a variation on Huffer's theme. Recalling America's decision to enter World War I after a long period of neutrality, he proposed a device that would symbolize Uncle Sam throwing his hat into the ring. His squadron mates liked the idea, and one of the pilots, Lieutenant Paul Wentworth, volunteered to draw up some tentative sketches of the design. The result of Wentworth's work became one of the most widely-recognized unit insignias. The squadron's artists immediately began to apply the Hat-in-the-Ring emblem to the squadron's Nieuports.

Even as they took brushes in hand, events occurred that brought the units of the 1st Pursuit Group Organization and Training Center into more active combat. The Germans launched a massive attack against the British lines to the north on 21 March 1918. The aircraft of the 94th and 95th sti11 lacked guns, and the staff in Paris reported that the pilots were not proficient enough to face the Germans. Villeneuve was too close to the front to be occupied by partially-trained units, so the center moved to a quieter sector. Someone in headquarters also realized that most of the pilots had not received any formal air-to-air gunnery training. Consequently, on 24 March 1918, most of the pilots of the 95th were ordered to the gunnery training school at Cazaux, in southwestern France. On 31 March the headquarters of the 1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center moved from Vi11eneuve-les-Vertus to Epiez. The 94th, reinforced by the few pilots of the 95th who had already received gunnery training, flew to Epiez on 1 April.

The center did not remain at Epiez for long. The field there was little more than a swamp. Aircraft regularly flipped over on landing, and the mud thrown back by flight leaders often broke the propellers of trailing planes during takeoffs. Because of pilot complaints and damage to the aircraft, the 94th left Epiez for Goncourt airfield near Toul. The 1st Pursuit Center remained at Epiez, without squadrons. When the 94th transferred to Toul it was temporarily assigned to the French VIII Army as an "Independent Air Unit."

The AEF air staff decided to transfer the 94th to Gencoult after determining that the squadron was ready to enter combat. Toul was an active sector, but the intensity of combat was low. The French used the region as a rest area for units rebuilding after an extended campaign and as a place to introduce newly-formed units into combat, and it seemed that the Germans used their side of the line for much the same purpose. Ground positions in the area were well-defined, with good communication links. French spotters at the front passed information about enemyaerial activity back to control centers and to the airfield, giving the 94th ample time to launch its aircraft.

The squadron's first patrols from Gencoult followed a pattern similar to that it had established at Villeneuve-les-Vertus. Two or three Americans in unarmed Nieuport 28s, led by an experienced French pilot, flew patrols against enemy long-range photographic reconnaissance aircraft. The Air Service staff reported that:

"The fact that the American airplanes had no machine guns was due to the shortage of these guns that prevailed on the Western Front at the time, but the fact that the area in which they worked was so far back of the lines as to make the danger of enemy attack negligible, coupled with the fact that the morale effect of their presence was in all probability sufficient to ensure the retreat of an isolated enemy photographic airplane, rendered this experience a valuable one."

The 94th, still under the operational control of the VIII French Army, moved from Epiez to Gencoult on 10 April 1918. At about the same time, the squadron finally received a consignment of machine guns for its aircraft. Mechanics quickly installed and tested the guns, and the pilots of the squadron prepared themselves for the time they would actually be able to do something about the enemy aircraft they harassed during their training flights. 16 Two days later, the commander of the Army Air Service, French VIII Army, issued orders making the 94th responsible for control of the air over a sector of the front from St Mihiel to Pont-a-Mousson. 11 It seems unlikely that the pilots of the 94th knew of the AEF air staff's judgment that the enemy pursuit units facing it were "neither aggressive, numerous, nor equipped with the best type of

machines."

On Sunday 14 April, the pilots of the 94th stood alert as an active combat unit for the first time. Captain David Peterson led the squadron's first patrol with Lieutenants Reed Chambers and Eddie Rickenbacker. Lieutenants Douglas Campbell and Alan Winslow waited on alert at the airfield. Peterson led his flight north from Gencoult at about 0600, heading for Pont-a-Mousson. The weather was bad, and by the time they reached their patrol altitude of 16,000 feet Peterson had turned back for the field with engine trouble. Rickenbacker took over flight lead, and he and Chambers made four circuits of a twenty-mile stretch of front between Pont-a-Mousson and St Mihiel. By the time they turned for home a heavy blanket of fog had settled over the area. Rickenbacker entered the clouds and immediately lost sight of Chambers. Rickenbacker descended to about 100 feet before recognizing a landmark that enabled him to turn for Gencoult, where he landed safely. Chambers had not yet returned. At about 0800, as Peterson chided Rickenbacker for flying off in deteriorating weather, the squadron operations officer received word that French spotters could hear German aircraft approaching the airfield. Campbell and Winslow took off immediately. Minutes after their departure a German Pfalz D-3 fell out of the clouds and crashed near the airfield. An Albatross D-5 followed it seconds later. The American pilots had no difficulty confirming these kills. Campbell received credit for the Pfalz, the 94th's first confirmed victory. Winslow was credited with the Albatross. The Americans landed about ten minutes after they scrambled. Both German pilots survived, and they reported that they had tried to intercept Rickenbacker's flight but became lost in the fog. Chambers eventually joined the festivities that followed.

Bad weather settled in, so the 94th remained on the ground for several days, basking in the glow of its "opening day" successes. Captain James N. Hall and Lieutenant Rickenbacker shared a kill on 29 April, the squadron's only other victory that month. As the 94th gained combat experience at the front, the 1st Pursuit Operations and Training Center added additional squadrons behind the lines. The pilots of the 95th completed their gunnery training at Cazaux and returned to Epiez on 22 April. The 27th and the 14 7th Aero Squadrons reported to Major Atkinson's

headquarters the same day. Both arrived without planes or pilots.

The 27th Aero Squadron was organized as Company K, 3d Provisional Aero Squadron, at Kelly Field, Texas, on 8 May 1917, almost fourteen weeks before the 94th and 95th were organized. On 15 June, Company K was redesignated the 21st Provisional Aero Squadron. The Signal Corps then discovered that it had organized another 21st Provisional Aero Squadron in California on the same day, so on 23 June 1917 the unit at Kelly Field was redesignated the 27th Aero Squadron, with Major Michael Davis as its first commander. In mid-August the squadron left Texas for Toronto, Canada, for advanced training. After about a month in Canada the 27th returned to Camp Hicks, near Fort Worth, Texas. Major Harold E. Hartney, a Canadian native and Royal Flying Corps veteran who had the dubious distinction of being one of Baron Manfred von Richthofen's early victims, became squadron commander on 2 January 1918. The 27th received orders to move to New York on 11 January, but it did not leave Texas for Garden City, New York, until the 23d. When the squadron arrived, medical officers immediately placed it under quarantine for scarlet fever. During this interlude the Army transferred two officers and sixty enlisted men to other units. Medical authorities lifted the quarantine on 3 February, and the squadron moved onto a troop ship. Squadron personnel lived aboard the transport until 26 February, when it sailed for Liverpool. The 27th arrived in England on 5 March 1918, the same day the 95th received its first Nieuport 28s in Paris and the 94th reported to Major Atkinson at Villeneuve. On 23 March the 27th arrived at the Aviation Training Center at Issoudun.

The 147th Aero Squadron arrived at Issoudun the next day. Organized on 11 November 1917 at Kelly Field under First Lieutenant John D. Morey, it completed its training and left New York for Liverpool on 5 March 1918. The squadron arrived on 18 March, proceeded to LeHavre on the 24th, and arrived at Issoudun late the same day. The 27th and the 14 7th trained together there for about a month. They reported to the 1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center on 22 April.

The AEF transferred the 95th Aero Squadron from the training center at Epiez to the 94th's airfield at Gencoult on 4 May, the same day it directed the 1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center to move from Villeneuve to Gencoult. As of that

date the center controlled three squadrons, the 27th, the 95th, and the 14 7th. The 27th and 14 7th were training at Epiez. The 95th found itself strung out on the road between Epiez and Gencoult. The 94th, still serving as an independent air unit with the French VIII Army, flew daily patrols from Gencoult.

The 1st Pursuit Group was organized at Gencoult, France, on 5 May 1918 under Major Bert M. Atkinson. Officers from the 1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center, which appears to have been dissolved at this point, filled most of the group staff positions. Headquarters, AEF assigned the 94th (relieved from its temporary assignment to the French VIII Army) and the 95th Aero Squadrons to the 1st Pursuit Group on the same day. The 1st Pursuit Group was, as its name suggests, the nation's first group-level fighter organization, but it was not the AEF's first flying group. That honor went to the 1st Corps Observation Group, organized in early April. The 27th and the 147th Aero Squadrons joined the group on 30 May.

The group suffered a devastating loss two weeks later. On 19 May Major Raoul Lufbery, part of the group staff but flying with the 94th, took off to intercept a German intruder. He attacked the two-seater, but the German gunner hit Lufbery's Nieuport in the gas tank. The aircraft burst into flames. Lufbery rode the blazing machine down to about 3,000 feet, where he apparently jumped out of the aircraft. He wore no parachute; French villagers who witnessed his fall reported that he struck a fence, staggered briefly to his feet, then fell over dead. Lufbery had received credit for seventeen kills at the time of his death, although he may have scored at least that many more that were never confirmed.

Lufbery's death stunned the group. He had helped to train many of the pilots, and they respected his courage and ability. The 94th and the 95th turned out in force for his funeral the next day. Lieutenant Kenneth P. Culbert of the 95th described the ceremony:

"As we marched to the grave, the sun was just sinking behind the mountain that rises so abruptly in front of Toul; the sky was a faultless blue and the air heavy with the scent of blossoms. An American and a French General led the procession, followed by a band which played the funeral march and "Nearer My God to Thee" so beautifully that I could hardly keep my eyes dry. There followed the officers of his squadron and my own, and after us, a group of Frenchmen, famous in the stories of this war, American officers of high rank, and two American companies of Infantry, separated by a French company. We passed before crowds of American nurses in their clean white uniforms and a throng of patients and French civilians. He was given a full military burial, with the salutes of the firing squad and the repetition of taps, one answering the other from the west .... Truly France and America had assembled to pay the last tribute to one of their bravest soldiers. My only prayer is that somehow, by some means, I may do as much for my country before I too go

west-ifin that direction I am to travel."

Lieutenant Culbert died in battle -"he went west" -the next day.

As the pilots of the 1st Pursuit Group helped lay Major Lufbery to rest, the members of the 27th Aero Squadron prepared themselves for their own initiation into combat. As part of this process, the pilots of the 27th met to consider a squadron insignia. They discussed several possibilities before Lieutenant Malcolm Gunn suggested a design he noticed in New York that struck his fancy. The Anheuser-Busch brewerv used (and continues to use) an eagle for its corporate logo. Gunn suggested that the 27th adopt a variation of this design, an eagle with outspread wings and talons diving on its prey. A Corporal Blumberg drew a sample design on 18 May, and the other members of the squadron decided it would make an ideal insignia. The squadron continues to use a variation of this design, although a falcon replaced theeagle in 1924.

The 27th (under Major Harold Hartney) and the 14 7th (under Major Geoffrey Bonnell) reported to Gencoult on 31 May. On the same day Lieutenant Douglas Campbell of the 94th became the nation's first "ace" when he shot down a German Rumpler observation plane over American lines near the village of Menial-La-Tours. The 94th took over the task of introducing the 27th to the intricacies of aerial combat, and pilots from the 94th led pilots of the 27th on their first patrols on 2 June. The 27th scored its first kill on 13 June, when four pilots combined to down an Albatross. By the end of June, as the 1st Pursuit Group prepared to move to a more active front, the group's four squadrons had accumulated twenty-seven confirmed kills, although pilots claimed to have shot down a total of fifty-eight enemy aircraft.

Group headquarters warned its units to be prepared to move on short notice in early June, when allied intelligence advised that a German offensive was imminent. On 26 June the group dispatched an advance party from the 27th to set up shop at Tonquin airfield, a site about 150 miles west of Toul and some twenty-five miles southwest of Chateau-Thierry. The 1st Pursuit Group headquarters transferred to Tonquin on 29 June, the same day the group's fifty-four Nieuport 28s made the flight without incident. The group mustered all its organizations the next day, and the four squadrons each made patrols over the area to familiarize the pilots with the terrain. Combat operations began on 1July.

The move to Tonquin marked the end of the 1st Pursuit Group's formative period and the beginning of four months of almost continuous front line service. By about 1 July the group's four squadrons were competent, combat-ready organizations. Since April they had accounted for twenty-seven kills (seventeen credited to the 94th, six to the 95th, and four to the 27th) in the quiet Toul sector. The squadrons learned to fly and fight together, and the group staff gained valuable experience controlling operations. The move to the Marne front exriosed the members ofthe 1st Pursuit Group

to a more demanding combat environment. The United States had so little combat aviation experience that most of the 1st Pursuit Group's actions during this period established precedents. The move from Toul to Tonquin, for example, was one of the Air Service's first large-scale tactical relocations in the face of the enemy. The AEF air staff considered the move to be so successful and so carefully executed that the official history suggested that it "might almost be considered a model." Atkinson organized the group into three echelons. The first formed an advance party, dispatched by ground transportation, that "comprised sufficient personnel from each squadron to care for the arriving airplanes, to install the necessary telephonic liaison and to arrange for billeting the enlisted and commissioned personnel.

The flying squadrons comprised the second echelon, while the third consisted of the maintenance and support personnel who launched the aircraft and brought remaining equipment to the new operating location. Atkinson devised a simple and efficient mobility procedure that was deemed a noteworthy innovation at the time.

The 1st Pursuit Group's operations on the Marne front marked the beginning of a period during which the Army Air Service began to develop operational and tactical procedures. When the group moved to the Marne front, it joined with the 1st Corps Observation Group and some French units to comprise the 1st Air Brigade, under Colonel Mitchell. Allied intelligence had detected a massive German buildup along the front and predicted a drive on Paris. To provide air cover for the upcoming offensive, the Germans deployed forty-six of their seventy-eight fighter squadrons, including Hermann Goering's Jagdeschwader I, the famed Richthofen Flying Circus. The quality and numbers of the opposition, along with the demanding requirements of the group's missions, forced the 1st Pursuit Group to adopt new tactics.

Colonel Mitchell assigned the 1st Pursuit Group three missions. The four squadrons worked to allow American observation aircraft to operate freely, to prevent enemy observation aircraft from completing their missions, and "to cause such other casualties and inflict such other material damage on the enemy as may be possible." The tactics adopted to protect American observation aircraft subsequently caused unnecessary losses, but the most immediate problem the group faced came from the numerically superior, aggressive, and experienced German squadrons. Lieutenant Harold Buckley of the 95th described the situation:

"... the halcyon days were over. No longer could we hunt in pairs deep in the enemy lines, delighted if the patrol produced a single enemy plane to chase. Gone were the days when we could dive into the fray with only a glance at our rear. There was trouble ahead. The action we craved was at hand; we could sense it in the air like an approaching storm .... The sky around us was filled with Fokkers; instead of a lone two-seater or two, we counted the enemy in droves of twelve, eighteen, and twenty."

The two-to-six plane formations of the Gencoult days gave way to squadron-strength patrols, twelve-to-sixteen plane formations divided into three flights. The lead flight attacked first, protected by the other two, which supported the first if the situation warranted. In practice, the flights frequently fought separate battles; the first attacked its target, usually enemy observation aircraft, while the other flights battled to keep escorting fighters off the backs of the lead section.

Doctrinal difficulties compounded the tactical problems created by the need to fly and fight in large formations. The group fared well when it flew offensive patrols against German observation aircraft, but it suffered heavy casualties when it flew close escort missions in support of the 1st Corps Observation Group. While the escort missions proved to be great morale boosters to the crews ofthe observation aircraft, the pursuit pilots were less enthusiastic. The observation aircraft were slower than the fighters and they attracted clouds of German fighters. Directed to fly in a protective formation around perhaps one or two observation aircraft, the escorts yielded the initiative to the Germans. "Denied the possibility of utilizing their maneuverability, speed or guns, they were easy prey. "

After suffering heavy observation and fighter losses, the American fliers adopted more successful tactics: the observation aircraft flew in larger formations, forcing attacking Germans to face the concentrated gunfire of their defensive armament. Escort support took the form of squadron-strength fighter sweeps flown ahead of and around the observation formations. This gave the fighters the initiative, since they could now attack as the Germans climbed toward the observation

formation. Epic air battles involving several squadrons on each side sometimes developed.

To further complicate the group's difficulties, a conversion from Nieuport 28s to Spad XIIIs began as the Marne campaign opened. The conversion took most of the month of July. The Nieuports were fragile aircraft, prone to shed fabric from their wings during violent maneuvers. Still, the 27th and the 14 7th preferred those "little fellows that responded more to the pilot's thought than to his touch" to what Major Hartney ofthe 27th called "those damned Spad machines. "41 The 94th and the 95th, on the other hand, had experienced more difficulty with Nieuports coming apart in mid-air and were delighted to get the Spads. The Spad was a sturdier and more powerful aircraft, but its Hispano-Suiza engine was more complex and more difficult to keep in tune than the Nieuport's Gnome rotary. The pilot transition and maintenance training process disrupted operations and effectively grounded each squadron in turn for several days, but the group flew what was available from day to day.

The Chateau Thierry (or Aisne-Marne) campaign comprised two phases that lasted from 15 July to about 6 August 1918. The long-awaited German offensive formed phase one, from 15 July through the 18th. The Germans gained some ground, but the well-prepared Allied armies blunted the German drive. The Allies launched a counteroffensive that lasted from 18 July through early August. The 1st Pursuit Group saw continuous action throughout the campaign, with the 27th and the 95th performing especially well. Pilots frequently flew three or four two-hour sorties each day, often in the face of heavy opposition. The group flew observation escort, counter-observation and ground attack missions, with an occasional reconnaissance sortie added to the flying schedule. Losses were heavy: in July the group destroyed twenty-nine German aircraft, but lost twenty-three.

Despite the difficulties encountered throughout the entire operation, the pilots of the 1st Pursuit Group "maintained their aggressive spirit, and attacked and fought successfully superior numbers of enemy planes."44 The Air Service gave the group high marks for its operations:

"While it is true that several of our balloons were burned; that our ground troops were repeatedly harassed by machine gun fire; and that our corps air service suffered more severe losses than they anticipated, it is also true that the 1st Pursuit Group carried the fighting into enemy territory; that our corps air service, despite its losses, was always able to do its work, even the work of deep photography, and that enemy attempts at photography and visual reconnaissance were seriously interfered with."

The group operated out of Tonquin and later Saints (occupied on 8 July) until about 20 August, supporting operations on the Chateau Thierry/Marne front and bringing its new Spads into service. During the last ten days of August, the group witnessed a number of changes as it prepared for its next campaign. On 21 August Major Hartney, commander of the 27th Aero Squadron, replaced Major Atkinson as commander of the 1st Pursuit Group. First Lieutenant Alfred A. Grant replaced Major Hartney as commanding officer of the 27th. Major Atkinson assumed command of the 1st Pursuit Wing, 1st Army, AEF. The wing included the 2nd and 3rd Pursuit Groups and the Day Bombardment Group.

Between about 22 August and 1 September, the group moved from Saints to Rembercourt, some twenty miles west of the town of St Mihiel on the Verdun/St Mihiel front. This move became part of the buildup for the American drive to eliminate the St Mihiel salient, and the group made the trip under the utmost secrecy. As the squadrons arrived at Rembercourt, they dispersed themselves around the field and camouflaged their aircraft and other equipment. The group kept its deployment hidden while it attemnted to mask the American buildup along its front from German

observation aircraft.

The attack began on 12 September; American forces eliminated the German positions in about four days. During the campaign the 1st Pursuit Group covered the front from Chatillion-sous-les-Cotes to St Mihiel, flying observation escort and anti-observation sorties. Extremely bad weather during the first three days of the offensive forced American aircraft to low levels, where they attacked German observation balloons and harassed troops on the ground. The attack caught the Germans in the midst of evacuating the salient, and American aircraft took a heavy toll of the retreating enemy. The weather improved on the 14th, but German air opposition centered on the southern flank of the salient covered by the 1st Pursuit Wing. As a result, the 1st Pursuit Group concentrated on ground attack throughout the campaign. Although ground operations ended on the 16th, air operations continued for another week to ten days.

As at Chateau Thierry, combat filled the 1st Pursuit Group's days. The pilots again flew many sorties each day, frequently landing only to take on more fuel and ammunition. The pace of action took its toll on both planes and pilots; as the ground

campaign drew to a close, Hartney ordered the group to reduce its operations to give mechanics time to make permanent repairs on the Spads, many of which were beginning to look like flying sieves from ground fire. The pilots were as worn out as the aircraft: on 16 September, Lieutenant John Jeffers of the 94th fell asleep while returning from a patrol. His Spad continued its flight on course, losing altitude slowly. Jeffers woke up in time to level out and crash on a hill not far from the airfield. He escaped injury.

Another short lull followed, as the American army redeployed for the Meuse-Argonne offensive. The 1st Pursuit Group rested and received replacements for the aircraft and pilots lost during the campaign. One noteworthy change of command occurred during this interval: on 25 September, Lieutenant Rickenbacker replaced Major Kenneth Marr as commanding officer ofthe 94th Aero Squadron.

Rickenbacker took command of a squadron "which seemingly had never lived up to its early promise." When he checked on the status of the squadron's kills, he found that the "presumptuous young 27th had suddenly taken a spurt, thanks to their brilliant Luke, and now led the Hat-in-the-Ring Squadron by six victories!" Rickenbacker immediately convened his pilots and announced that "no other American squadron at the front would ever again be permitted to approach our margin of supremacy." Within a week, the 94th had overtaken the 27th and never relinquished the lead.

After his talk with the pilots, Rickenbacker next approached the squadron's mechanics who, he reported, "felt the disgrace of being second more keenly than did we pilots." Not surprisingly, Rickenbacker later noted that from that time on the

squadron's aircraft were always in top mechanical condition. Lieutenant Rickenbacker resolved to lead by example. A squadron commander had administrative responsibilities, but they interested him less than the real matter at hand. He passed these duties to subordinates. To avoid the red-tape business at the aerodrome - the making out of reports, ordering materials and seeing that they came in on time, looking after details of the mess, the hangars and the comfort of the enlisted men - all this work must be placed under competent men, if I expect to stay in the air and lead patrols. Accordingly I gave this important matter my attention early next morning. And the success of my appointments was such that from that day on I never spent more than thirty minutes a day upon the ground business connected with 94's

operation.

At about this time - late September 1918 - the 1st Pursuit Group reached its operational peak. All four squadrons were experienced, and staff officers at all levels had served through at least two major campaigns. As of the end of September, after about six months of combat, the ~oup was credited with one hundred kills, achieved at a cost of fifty-seven casualties. 5 Major Hartney, the group commander, "found in the other squadrons the same ultra-fine quality of officers and men of which I had been so proud in the 27th, courageous, well-trained, decent, loyal and intelligent." During the last seven weeks of the war the 1st Pursuit Group scored an additional 102 kills at a cost of fifteen of its pilots.

The United States Army launched its final offensive of the war on 26 September, when the American First Army began the Meuse-Argonne offensive. The terrain favored the defenders, and the Germans had organized a formidable defensive

system. By this time the AEF staff had come to appreciate "the morale effect of aviation," ... and it was felt that the necessity of supremacy of the air was needed more by American arms in these operations than perhaps ever before, to produce the greatest results. It needed the morale supremacy, so easily enhanced by a predominance of ground troops, of low-flying airplanes to carry Americans over the awful terrain of the Meuse under trying weather conditions.

The 1st Army air staff assigned the 1st Pursuit Group the task of providing that low-level support during the offensive. The staff ordered the group to clear the front of enemy observation balloons and low-flying aircraft. The 1st Pursuit Wing, especially the 2nd and 3rd Pursuit Groups, provided top-cover for the 1st Pursuit Group. It also provided escort for American bombers and observation aircraft. The staff knew that the decision to commit roughly one-third of the fighter force to tactical air support might jeopardize air superiority, but they believed that it was "more important that

enemy aviation, including balloons and airplanes, low and full in sight of the advancing troops, should be destroyed at all costs."

Committed to low-altitude defense suppression and air support operations, the 1st Pursuit Group reverted to the small formations and stalking tactics that characterized its earlier service on the Toul front. The group flew most of its missions during the last seven weeks of the war at low altitude, attacking enemy observation aircraft and heavily-defended observation balloons, although pilots showed no reluctance to take on enemy fighters that slipped past the group's top cover. Perhaps no one was any better at this dangerous work than Lieutenant Frank Luke of the 27th. Luke specialized in attacking enemy balloons, a risky process since the balloons floated on tethers at known altitudes and enjoyed the protection of aircraft and mobile flak batteries. Luke attacked these balloons fearlessly. His only close friend in the 27th, Lieutenant Joseph Wehner, often flew top cover while Luke went after a balloon. Neither attracted any particular attention until the start of the Meuse-Argonne campaign!f when their work against the German balloons broughtthem both fame and death.

On 18 September, Luke and Wehner were attacking a balloon line when Wehner noticed seven Fokkers stalking Luke's Spad. Wehner threw himself at the Germans, disrupting their attack and alerting Luke. The odds were too great, however, and Wehner was killed. Luke tore into the Germans, and in about ten minutes destroyed three balloons and two of the Fokkers. Luke was never noted for his caution, but he showed a tendency to take even peater risks after Wehner's death.

Hartney grounded him for a time, but to no avail. On Sunday, 29 September, Luke took off alone to take on enemy balloons along the front. At 1905 he destroyed one near Dun-sur-Meuse. Another fell shortly thereafter at Buiere Farm. He then shot down two pursuing Fokkers before claiming a third balloon near Milly at 1912. Badly wounded and flying a damaged plane, Luke strafed a German unit he found in Murvaux. He then made a forced landing near the town. He drew his pistol and fired on the German troops sent to capture him. Luke died in the ensuing gun battle. He was later awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions on this mission.

The 1st Pursuit Group continued to fly low-level missions until the end of the war. On 7 October, the 185th Night Pursuit Squadron, led by Lieutenant Seth Low, was assigned to the Group. The 185th was organized at Kelly Field on 11 November 1917 and trained as a night fighter unit after arriving in France. Its prey were the giant German bombers that made nightly forays into Allied territory, and its tactics were simple: after receiving word that the Germans were in the vicinity, a pilot took off, climbed for altitude, and shut off his engine to listen for the intruders. When a pilot felt he was too low he restarted his engine, climbed, cut the engine again, and resumed his aural search. The squadron achieved no confirmed kills during the month it was at the front but Major Hartney may have shot down a German bomber using this

method.

The 1st Pursuit Group achieved remarkable success during the last six weeks of the war. In October the group's five squadrons destroyed fifty-six of the enemy at a cost of thirteen American planes. The 94th set the pace with twenty-eight kills. November was an even more remarkable month. During the first ten days of the month the four day-squadrons destroyed forty-five enemy aircraft or balloons without a loss. The 94th, which claimed America's first World War I kill, also received credit for the last aerial victory, a Fokker destroyed by Major Maxwell Kirby on 10 November. The

Armistice took effect the next day.

The 1st Pursuit Group ended the war with 202 confirmed kills. Rickenbacker was America's "Ace-of-Aces" with twenty-six kills, twenty-two aircraft and four balloons. Luke scored eighteen kills, four aircraft and fourteen balloons, while Lufbery received credit for seventeen kills, all aircraft. By squadron, the 94th received credit for sixty-seven and a half kills; the 27th, fifty-six; the 95th, forty-seven and a half; and the 14 7th, thirty-one. The squadrons achieved these totals at a cost of

seventy-two American casualties, killed, wounded or captured. The 27th lost twenty-two; the 95th, nineteen; the 94th, eighteen; the 14 7th, ten; and the 185th, three. The four day-squadrons of the 1st Pursuit Group accounted for approximately 38 percent of the Army Air Service's 526 confirmed victories in World War I.

On 17 November orders from the American staff in Paris relieved the 94th Aero Squadron from its assignment to the 1st Pursuit Group, assigned it to the 5th Pursuit Group, Third Army, and directed it to prepare to accompany elements of the American Army across the Rhine. The squadron departed Rembercourt on 25 November and occupied the former German airfield at Moors four days later. On 7 December advanced parties of the group's remaining squadrons departed Rembercourt for Colombey-les-Belles, where the 1st Pursuit Group disbanded on 24 December 1918. The 95th returned to the United States on 1 March 1919 and demobilized at Garden City, New York, on 18 March. The 27th and the 147th arrived at Hoboken the next day. The 27th ended the war as it began it, in quarantine in New York, this time with the 147th. The two squadrons demobilized in April. The 94th ended its service with the Third Army on 9 April 1919 and arrived at Hoboken on 31 May. It demobilized at New York on 1 June. Even as the World War I squadrons completed their demobilization, however, the War Department began organizing a new 1st Pursuit Group at Selfridge Field, Michigan.

Major Atkinson wasted little time in organizing a staff for the "1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center" established at Villeneuve-les-Vertus on 16 January 1918. He appointed Captain Roosevelt adjutant and Captain Rankin supply officer, and they set to work. Despite their good intentions, the conditions Atkinson, Roosevelt, and Rankin encountered in France complicated their work. The American staff in Paris had assured them that Villeneuve-les-Vertus was a spacious, well-equipped airfield ready to receive the three pursuit squadrons then completing the training course at the advanced training school at Issoudun, where American pilots transitioned from the trainers they flew in the United States to the high performance fighters they would fly at the front. Combat-ready Spads supposedly sat at French factories, awaiting the arrival of the pilots from Issoudun to ferry them to the front. The Americans found, to their chagrin, that the staff in Paris had little grasp of the actual situation at the front.

Villeneuve proved to be a first-rate airfield, but the French 12th Groupe de Combat occupied all its facilities. The squadrons training at Issoudun were far from being ready for combat at the front. As for the Spads, the French suggested that they might be able to supply some in six months or so, but French aviation officers reported that they had few they could spare at the time.

Captain Rankin, the supply officer, sized up the situation. He used some of his funds to purchase a quantity of champagne, and with its help and a little innovative bargaining, he obtained shop space from the French unit at Villeneuve-les-Vertus. By the middle of February, about a month after their arrival, Major Atkinson and his growing Training Center staff had managed to build or borrow a barracks and hangar space for thirty-six aircraft. When Atkinson reported that these limited facilities were available, the American staff in Paris dispatched to the airdrome the squadrons that would soon make up the 1st Pursuit Group. The 95th Aero Squadron reported on18 February 1918. The 94th Aero Squadron rolled into camp two weeks later, on 4 March. Neither squadron possessed any aircraft, but Major Atkinson and Captain James E. Miller commander of the 95th, began pursuing some promising leads.

The 94th and 95th Aero Squadrons had trained and travelled together since their organization on 20 August 1917, at Kelly Field, Texas. First Lieutenant J. Bayard H. Smith became the first commander of the 94th, while First Lieutenant Fred Natcher led the 95th. When the two squadrons boarded a train at Kelly Field on I - 20 September 1917 for the trip to Mineola, New York, they consisted entirely of the enlisted echelon that would form the squadron's ground support element. Arriving at Mineola on 5 October, the squadrons reported directly to Aviation Mobilization Camp No. 2. Each unit completed training there in about three weeks and proceeded to Hoboken, New Jersey, where, on 27 October 1917, they boarded a ship for the trip to Europe. The two squadrons arrived at Liverpool on 10 November, spent fourteen hours in a rest camp, boarded a steamer at Southampton, and sailed for France on 12 November. The 94th and 95th entered camp at LeHavre the next day, but their travels were not quite over. On 15 November the 95th moved to the Aviation Training Center at Issoudun. On 18 November the 94th moved to Paris, where it divided into seven detachments that immediately began advanced maintenance training in the region's airframe and aero-engine plants. The 94th reassembled in Paris and departed for Issoudun on 24 January 1918.

After the 95th's personnel arrived at Issoudun in November, they received advanced training on the same types of aircraft they would operate at the front. The 95th thus found itself well along in its training when the 1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center announced its readiness to receive units in mid-February, and it became the first unit to be attached to the center. The 94th made good progress at Issoudun, however, and it reported to Villeneuve not long after the 95th. Captain Miller remained in command of the 95th when it arrived at Villeneuve; Major John F. Huffer commanded the 94th.

The 1st Pursuit Center controlled a pair of combat units, but neither was ready for combat. The newly-assigned pilots and maintenance personnel were eager, but they had little with which to work. Major Atkinson had obtained only a handful of

aircraft from the French, all Nieuport 28s, France's second-line fighter. The French reported that they had no surplus Spads available to equip the Americans, so Atkinson and his staff agreed that the units would see action sooner if the Americans accepted the more readily available Nieuport. On 26 February they received word that thirty-six Nieuports were waiting to be picked up at a factory near Paris. A contingent of pilots departed within hours, but bad weather delayed their return. The weather broke on 5 March, allowing fifteen pilots to take off for Villeneuve. Only six successfully completed the return flight that day. Weather and mechanical difficulties forced the others to land along the route. All the Nieuports reached Villeneuve by 8 March, and Atkinson assigned most of them to the 95th.

Even as the 95th lay claim to the first sizable contingent of aircraft, the 94th made its bid for fame by launching, on 6 March 1918, the first patrol flown by an all-American squadron in France. At 0815, Major Raoul Lufbery led two young first lieutenants, Douglas Campbell and Edward V. Rickenbacker, on a two-hour patrol near Rheims. A German antiaircraft battery challenged the flight, but it encountered no aerial opposition, a fortunate circumstance, since neither Campbell's nor Rickenbacker's aircraft carried any armament. The two neophytes believed they had flown an uneventful patrol. To their surprise, the more experienced Lufbery calmly pointed out that he had spotted no less than ten Spads, four German fighters, and a German two-seat observation aircraft during the patrol. He also showed Rickenbacker holes in the fabric skin of the younger pilot's aircraft, a reminder of their brush with the German battery.

The 95th made its first flights on 8 March 1918. These missions followed the pattern the 94th established during its first sorties. An experienced pilot, frequently either Major Lufbery or someone from the French group, led two or three Americans on a patrol over a quiet sector of the front. The Americans made great sport of these unarmed patrols, but the French expressed more concern. The initial patrols proved uneventful, but they were not without their risks. The frail Nieuports had several mechanical and structural faults, and engine trouble in a Nieuport contributed to the 1st Pursuit Center's first combat loss.

Captain Miller, commander of the 95th, experienced engine trouble on a training flight on 8 March 1918. He landed safely at Coincy and returned to Villeneuve by truck. On 10 March he returned to Coincy to pick up his aircraft. On the way back to the Center, Miller stopped to visit some friends at the airfield at Coligny, where he borrowed a Spad and flew a patrol over Rheims in the company of two other pilots. German fighters attacked the flight; Miller died in the ensuing dogfight. Captain Seth Low assumed command of the 95th, but Major Davenport Johnson, who flew with Miller on his final flight, replaced Low on 15 March.

As training operations continued and the pilots gained proficiency, morale in both squadrons soared. The A11ies anticipated a German offensive on the Western Front, and the members of the two squadrons sensed that their real baptism of fire was at hand. With this prospect in mind, the members of the 94th began to discuss the design of a unit emblem. The 94th's commander, Major Huffer, suggested that the squadron use Uncle Sam's stovepipe hat. Lieutenant Paul Walters, squadron medical officer, suggested a variation on Huffer's theme. Recalling America's decision to enter World War I after a long period of neutrality, he proposed a device that would symbolize Uncle Sam throwing his hat into the ring. His squadron mates liked the idea, and one of the pilots, Lieutenant Paul Wentworth, volunteered to draw up some tentative sketches of the design. The result of Wentworth's work became one of the most widely-recognized unit insignias. The squadron's artists immediately began to apply the Hat-in-the-Ring emblem to the squadron's Nieuports.

Even as they took brushes in hand, events occurred that brought the units of the 1st Pursuit Group Organization and Training Center into more active combat. The Germans launched a massive attack against the British lines to the north on 21 March 1918. The aircraft of the 94th and 95th sti11 lacked guns, and the staff in Paris reported that the pilots were not proficient enough to face the Germans. Villeneuve was too close to the front to be occupied by partially-trained units, so the center moved to a quieter sector. Someone in headquarters also realized that most of the pilots had not received any formal air-to-air gunnery training. Consequently, on 24 March 1918, most of the pilots of the 95th were ordered to the gunnery training school at Cazaux, in southwestern France. On 31 March the headquarters of the 1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center moved from Vi11eneuve-les-Vertus to Epiez. The 94th, reinforced by the few pilots of the 95th who had already received gunnery training, flew to Epiez on 1 April.

The center did not remain at Epiez for long. The field there was little more than a swamp. Aircraft regularly flipped over on landing, and the mud thrown back by flight leaders often broke the propellers of trailing planes during takeoffs. Because of pilot complaints and damage to the aircraft, the 94th left Epiez for Goncourt airfield near Toul. The 1st Pursuit Center remained at Epiez, without squadrons. When the 94th transferred to Toul it was temporarily assigned to the French VIII Army as an "Independent Air Unit."

The AEF air staff decided to transfer the 94th to Gencoult after determining that the squadron was ready to enter combat. Toul was an active sector, but the intensity of combat was low. The French used the region as a rest area for units rebuilding after an extended campaign and as a place to introduce newly-formed units into combat, and it seemed that the Germans used their side of the line for much the same purpose. Ground positions in the area were well-defined, with good communication links. French spotters at the front passed information about enemyaerial activity back to control centers and to the airfield, giving the 94th ample time to launch its aircraft.

The squadron's first patrols from Gencoult followed a pattern similar to that it had established at Villeneuve-les-Vertus. Two or three Americans in unarmed Nieuport 28s, led by an experienced French pilot, flew patrols against enemy long-range photographic reconnaissance aircraft. The Air Service staff reported that:

"The fact that the American airplanes had no machine guns was due to the shortage of these guns that prevailed on the Western Front at the time, but the fact that the area in which they worked was so far back of the lines as to make the danger of enemy attack negligible, coupled with the fact that the morale effect of their presence was in all probability sufficient to ensure the retreat of an isolated enemy photographic airplane, rendered this experience a valuable one."

The 94th, still under the operational control of the VIII French Army, moved from Epiez to Gencoult on 10 April 1918. At about the same time, the squadron finally received a consignment of machine guns for its aircraft. Mechanics quickly installed and tested the guns, and the pilots of the squadron prepared themselves for the time they would actually be able to do something about the enemy aircraft they harassed during their training flights. 16 Two days later, the commander of the Army Air Service, French VIII Army, issued orders making the 94th responsible for control of the air over a sector of the front from St Mihiel to Pont-a-Mousson. 11 It seems unlikely that the pilots of the 94th knew of the AEF air staff's judgment that the enemy pursuit units facing it were "neither aggressive, numerous, nor equipped with the best type of

machines."

On Sunday 14 April, the pilots of the 94th stood alert as an active combat unit for the first time. Captain David Peterson led the squadron's first patrol with Lieutenants Reed Chambers and Eddie Rickenbacker. Lieutenants Douglas Campbell and Alan Winslow waited on alert at the airfield. Peterson led his flight north from Gencoult at about 0600, heading for Pont-a-Mousson. The weather was bad, and by the time they reached their patrol altitude of 16,000 feet Peterson had turned back for the field with engine trouble. Rickenbacker took over flight lead, and he and Chambers made four circuits of a twenty-mile stretch of front between Pont-a-Mousson and St Mihiel. By the time they turned for home a heavy blanket of fog had settled over the area. Rickenbacker entered the clouds and immediately lost sight of Chambers. Rickenbacker descended to about 100 feet before recognizing a landmark that enabled him to turn for Gencoult, where he landed safely. Chambers had not yet returned. At about 0800, as Peterson chided Rickenbacker for flying off in deteriorating weather, the squadron operations officer received word that French spotters could hear German aircraft approaching the airfield. Campbell and Winslow took off immediately. Minutes after their departure a German Pfalz D-3 fell out of the clouds and crashed near the airfield. An Albatross D-5 followed it seconds later. The American pilots had no difficulty confirming these kills. Campbell received credit for the Pfalz, the 94th's first confirmed victory. Winslow was credited with the Albatross. The Americans landed about ten minutes after they scrambled. Both German pilots survived, and they reported that they had tried to intercept Rickenbacker's flight but became lost in the fog. Chambers eventually joined the festivities that followed.

Bad weather settled in, so the 94th remained on the ground for several days, basking in the glow of its "opening day" successes. Captain James N. Hall and Lieutenant Rickenbacker shared a kill on 29 April, the squadron's only other victory that month. As the 94th gained combat experience at the front, the 1st Pursuit Operations and Training Center added additional squadrons behind the lines. The pilots of the 95th completed their gunnery training at Cazaux and returned to Epiez on 22 April. The 27th and the 14 7th Aero Squadrons reported to Major Atkinson's

headquarters the same day. Both arrived without planes or pilots.

The 27th Aero Squadron was organized as Company K, 3d Provisional Aero Squadron, at Kelly Field, Texas, on 8 May 1917, almost fourteen weeks before the 94th and 95th were organized. On 15 June, Company K was redesignated the 21st Provisional Aero Squadron. The Signal Corps then discovered that it had organized another 21st Provisional Aero Squadron in California on the same day, so on 23 June 1917 the unit at Kelly Field was redesignated the 27th Aero Squadron, with Major Michael Davis as its first commander. In mid-August the squadron left Texas for Toronto, Canada, for advanced training. After about a month in Canada the 27th returned to Camp Hicks, near Fort Worth, Texas. Major Harold E. Hartney, a Canadian native and Royal Flying Corps veteran who had the dubious distinction of being one of Baron Manfred von Richthofen's early victims, became squadron commander on 2 January 1918. The 27th received orders to move to New York on 11 January, but it did not leave Texas for Garden City, New York, until the 23d. When the squadron arrived, medical officers immediately placed it under quarantine for scarlet fever. During this interlude the Army transferred two officers and sixty enlisted men to other units. Medical authorities lifted the quarantine on 3 February, and the squadron moved onto a troop ship. Squadron personnel lived aboard the transport until 26 February, when it sailed for Liverpool. The 27th arrived in England on 5 March 1918, the same day the 95th received its first Nieuport 28s in Paris and the 94th reported to Major Atkinson at Villeneuve. On 23 March the 27th arrived at the Aviation Training Center at Issoudun.

The 147th Aero Squadron arrived at Issoudun the next day. Organized on 11 November 1917 at Kelly Field under First Lieutenant John D. Morey, it completed its training and left New York for Liverpool on 5 March 1918. The squadron arrived on 18 March, proceeded to LeHavre on the 24th, and arrived at Issoudun late the same day. The 27th and the 14 7th trained together there for about a month. They reported to the 1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center on 22 April.

The AEF transferred the 95th Aero Squadron from the training center at Epiez to the 94th's airfield at Gencoult on 4 May, the same day it directed the 1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center to move from Villeneuve to Gencoult. As of that

date the center controlled three squadrons, the 27th, the 95th, and the 14 7th. The 27th and 14 7th were training at Epiez. The 95th found itself strung out on the road between Epiez and Gencoult. The 94th, still serving as an independent air unit with the French VIII Army, flew daily patrols from Gencoult.

The 1st Pursuit Group was organized at Gencoult, France, on 5 May 1918 under Major Bert M. Atkinson. Officers from the 1st Pursuit Organization and Training Center, which appears to have been dissolved at this point, filled most of the group staff positions. Headquarters, AEF assigned the 94th (relieved from its temporary assignment to the French VIII Army) and the 95th Aero Squadrons to the 1st Pursuit Group on the same day. The 1st Pursuit Group was, as its name suggests, the nation's first group-level fighter organization, but it was not the AEF's first flying group. That honor went to the 1st Corps Observation Group, organized in early April. The 27th and the 147th Aero Squadrons joined the group on 30 May.

The group suffered a devastating loss two weeks later. On 19 May Major Raoul Lufbery, part of the group staff but flying with the 94th, took off to intercept a German intruder. He attacked the two-seater, but the German gunner hit Lufbery's Nieuport in the gas tank. The aircraft burst into flames. Lufbery rode the blazing machine down to about 3,000 feet, where he apparently jumped out of the aircraft. He wore no parachute; French villagers who witnessed his fall reported that he struck a fence, staggered briefly to his feet, then fell over dead. Lufbery had received credit for seventeen kills at the time of his death, although he may have scored at least that many more that were never confirmed.

Lufbery's death stunned the group. He had helped to train many of the pilots, and they respected his courage and ability. The 94th and the 95th turned out in force for his funeral the next day. Lieutenant Kenneth P. Culbert of the 95th described the ceremony:

"As we marched to the grave, the sun was just sinking behind the mountain that rises so abruptly in front of Toul; the sky was a faultless blue and the air heavy with the scent of blossoms. An American and a French General led the procession, followed by a band which played the funeral march and "Nearer My God to Thee" so beautifully that I could hardly keep my eyes dry. There followed the officers of his squadron and my own, and after us, a group of Frenchmen, famous in the stories of this war, American officers of high rank, and two American companies of Infantry, separated by a French company. We passed before crowds of American nurses in their clean white uniforms and a throng of patients and French civilians. He was given a full military burial, with the salutes of the firing squad and the repetition of taps, one answering the other from the west .... Truly France and America had assembled to pay the last tribute to one of their bravest soldiers. My only prayer is that somehow, by some means, I may do as much for my country before I too go

west-ifin that direction I am to travel."

Lieutenant Culbert died in battle -"he went west" -the next day.

As the pilots of the 1st Pursuit Group helped lay Major Lufbery to rest, the members of the 27th Aero Squadron prepared themselves for their own initiation into combat. As part of this process, the pilots of the 27th met to consider a squadron insignia. They discussed several possibilities before Lieutenant Malcolm Gunn suggested a design he noticed in New York that struck his fancy. The Anheuser-Busch brewerv used (and continues to use) an eagle for its corporate logo. Gunn suggested that the 27th adopt a variation of this design, an eagle with outspread wings and talons diving on its prey. A Corporal Blumberg drew a sample design on 18 May, and the other members of the squadron decided it would make an ideal insignia. The squadron continues to use a variation of this design, although a falcon replaced theeagle in 1924.

The 27th (under Major Harold Hartney) and the 14 7th (under Major Geoffrey Bonnell) reported to Gencoult on 31 May. On the same day Lieutenant Douglas Campbell of the 94th became the nation's first "ace" when he shot down a German Rumpler observation plane over American lines near the village of Menial-La-Tours. The 94th took over the task of introducing the 27th to the intricacies of aerial combat, and pilots from the 94th led pilots of the 27th on their first patrols on 2 June. The 27th scored its first kill on 13 June, when four pilots combined to down an Albatross. By the end of June, as the 1st Pursuit Group prepared to move to a more active front, the group's four squadrons had accumulated twenty-seven confirmed kills, although pilots claimed to have shot down a total of fifty-eight enemy aircraft.

Group headquarters warned its units to be prepared to move on short notice in early June, when allied intelligence advised that a German offensive was imminent. On 26 June the group dispatched an advance party from the 27th to set up shop at Tonquin airfield, a site about 150 miles west of Toul and some twenty-five miles southwest of Chateau-Thierry. The 1st Pursuit Group headquarters transferred to Tonquin on 29 June, the same day the group's fifty-four Nieuport 28s made the flight without incident. The group mustered all its organizations the next day, and the four squadrons each made patrols over the area to familiarize the pilots with the terrain. Combat operations began on 1July.

The move to Tonquin marked the end of the 1st Pursuit Group's formative period and the beginning of four months of almost continuous front line service. By about 1 July the group's four squadrons were competent, combat-ready organizations. Since April they had accounted for twenty-seven kills (seventeen credited to the 94th, six to the 95th, and four to the 27th) in the quiet Toul sector. The squadrons learned to fly and fight together, and the group staff gained valuable experience controlling operations. The move to the Marne front exriosed the members ofthe 1st Pursuit Group

to a more demanding combat environment. The United States had so little combat aviation experience that most of the 1st Pursuit Group's actions during this period established precedents. The move from Toul to Tonquin, for example, was one of the Air Service's first large-scale tactical relocations in the face of the enemy. The AEF air staff considered the move to be so successful and so carefully executed that the official history suggested that it "might almost be considered a model." Atkinson organized the group into three echelons. The first formed an advance party, dispatched by ground transportation, that "comprised sufficient personnel from each squadron to care for the arriving airplanes, to install the necessary telephonic liaison and to arrange for billeting the enlisted and commissioned personnel.

The flying squadrons comprised the second echelon, while the third consisted of the maintenance and support personnel who launched the aircraft and brought remaining equipment to the new operating location. Atkinson devised a simple and efficient mobility procedure that was deemed a noteworthy innovation at the time.

The 1st Pursuit Group's operations on the Marne front marked the beginning of a period during which the Army Air Service began to develop operational and tactical procedures. When the group moved to the Marne front, it joined with the 1st Corps Observation Group and some French units to comprise the 1st Air Brigade, under Colonel Mitchell. Allied intelligence had detected a massive German buildup along the front and predicted a drive on Paris. To provide air cover for the upcoming offensive, the Germans deployed forty-six of their seventy-eight fighter squadrons, including Hermann Goering's Jagdeschwader I, the famed Richthofen Flying Circus. The quality and numbers of the opposition, along with the demanding requirements of the group's missions, forced the 1st Pursuit Group to adopt new tactics.

Colonel Mitchell assigned the 1st Pursuit Group three missions. The four squadrons worked to allow American observation aircraft to operate freely, to prevent enemy observation aircraft from completing their missions, and "to cause such other casualties and inflict such other material damage on the enemy as may be possible." The tactics adopted to protect American observation aircraft subsequently caused unnecessary losses, but the most immediate problem the group faced came from the numerically superior, aggressive, and experienced German squadrons. Lieutenant Harold Buckley of the 95th described the situation:

"... the halcyon days were over. No longer could we hunt in pairs deep in the enemy lines, delighted if the patrol produced a single enemy plane to chase. Gone were the days when we could dive into the fray with only a glance at our rear. There was trouble ahead. The action we craved was at hand; we could sense it in the air like an approaching storm .... The sky around us was filled with Fokkers; instead of a lone two-seater or two, we counted the enemy in droves of twelve, eighteen, and twenty."

The two-to-six plane formations of the Gencoult days gave way to squadron-strength patrols, twelve-to-sixteen plane formations divided into three flights. The lead flight attacked first, protected by the other two, which supported the first if the situation warranted. In practice, the flights frequently fought separate battles; the first attacked its target, usually enemy observation aircraft, while the other flights battled to keep escorting fighters off the backs of the lead section.

Doctrinal difficulties compounded the tactical problems created by the need to fly and fight in large formations. The group fared well when it flew offensive patrols against German observation aircraft, but it suffered heavy casualties when it flew close escort missions in support of the 1st Corps Observation Group. While the escort missions proved to be great morale boosters to the crews ofthe observation aircraft, the pursuit pilots were less enthusiastic. The observation aircraft were slower than the fighters and they attracted clouds of German fighters. Directed to fly in a protective formation around perhaps one or two observation aircraft, the escorts yielded the initiative to the Germans. "Denied the possibility of utilizing their maneuverability, speed or guns, they were easy prey. "

After suffering heavy observation and fighter losses, the American fliers adopted more successful tactics: the observation aircraft flew in larger formations, forcing attacking Germans to face the concentrated gunfire of their defensive armament. Escort support took the form of squadron-strength fighter sweeps flown ahead of and around the observation formations. This gave the fighters the initiative, since they could now attack as the Germans climbed toward the observation

formation. Epic air battles involving several squadrons on each side sometimes developed.

To further complicate the group's difficulties, a conversion from Nieuport 28s to Spad XIIIs began as the Marne campaign opened. The conversion took most of the month of July. The Nieuports were fragile aircraft, prone to shed fabric from their wings during violent maneuvers. Still, the 27th and the 14 7th preferred those "little fellows that responded more to the pilot's thought than to his touch" to what Major Hartney ofthe 27th called "those damned Spad machines. "41 The 94th and the 95th, on the other hand, had experienced more difficulty with Nieuports coming apart in mid-air and were delighted to get the Spads. The Spad was a sturdier and more powerful aircraft, but its Hispano-Suiza engine was more complex and more difficult to keep in tune than the Nieuport's Gnome rotary. The pilot transition and maintenance training process disrupted operations and effectively grounded each squadron in turn for several days, but the group flew what was available from day to day.

The Chateau Thierry (or Aisne-Marne) campaign comprised two phases that lasted from 15 July to about 6 August 1918. The long-awaited German offensive formed phase one, from 15 July through the 18th. The Germans gained some ground, but the well-prepared Allied armies blunted the German drive. The Allies launched a counteroffensive that lasted from 18 July through early August. The 1st Pursuit Group saw continuous action throughout the campaign, with the 27th and the 95th performing especially well. Pilots frequently flew three or four two-hour sorties each day, often in the face of heavy opposition. The group flew observation escort, counter-observation and ground attack missions, with an occasional reconnaissance sortie added to the flying schedule. Losses were heavy: in July the group destroyed twenty-nine German aircraft, but lost twenty-three.

Despite the difficulties encountered throughout the entire operation, the pilots of the 1st Pursuit Group "maintained their aggressive spirit, and attacked and fought successfully superior numbers of enemy planes."44 The Air Service gave the group high marks for its operations:

"While it is true that several of our balloons were burned; that our ground troops were repeatedly harassed by machine gun fire; and that our corps air service suffered more severe losses than they anticipated, it is also true that the 1st Pursuit Group carried the fighting into enemy territory; that our corps air service, despite its losses, was always able to do its work, even the work of deep photography, and that enemy attempts at photography and visual reconnaissance were seriously interfered with."

The group operated out of Tonquin and later Saints (occupied on 8 July) until about 20 August, supporting operations on the Chateau Thierry/Marne front and bringing its new Spads into service. During the last ten days of August, the group witnessed a number of changes as it prepared for its next campaign. On 21 August Major Hartney, commander of the 27th Aero Squadron, replaced Major Atkinson as commander of the 1st Pursuit Group. First Lieutenant Alfred A. Grant replaced Major Hartney as commanding officer of the 27th. Major Atkinson assumed command of the 1st Pursuit Wing, 1st Army, AEF. The wing included the 2nd and 3rd Pursuit Groups and the Day Bombardment Group.

Between about 22 August and 1 September, the group moved from Saints to Rembercourt, some twenty miles west of the town of St Mihiel on the Verdun/St Mihiel front. This move became part of the buildup for the American drive to eliminate the St Mihiel salient, and the group made the trip under the utmost secrecy. As the squadrons arrived at Rembercourt, they dispersed themselves around the field and camouflaged their aircraft and other equipment. The group kept its deployment hidden while it attemnted to mask the American buildup along its front from German

observation aircraft.

The attack began on 12 September; American forces eliminated the German positions in about four days. During the campaign the 1st Pursuit Group covered the front from Chatillion-sous-les-Cotes to St Mihiel, flying observation escort and anti-observation sorties. Extremely bad weather during the first three days of the offensive forced American aircraft to low levels, where they attacked German observation balloons and harassed troops on the ground. The attack caught the Germans in the midst of evacuating the salient, and American aircraft took a heavy toll of the retreating enemy. The weather improved on the 14th, but German air opposition centered on the southern flank of the salient covered by the 1st Pursuit Wing. As a result, the 1st Pursuit Group concentrated on ground attack throughout the campaign. Although ground operations ended on the 16th, air operations continued for another week to ten days.

As at Chateau Thierry, combat filled the 1st Pursuit Group's days. The pilots again flew many sorties each day, frequently landing only to take on more fuel and ammunition. The pace of action took its toll on both planes and pilots; as the ground

campaign drew to a close, Hartney ordered the group to reduce its operations to give mechanics time to make permanent repairs on the Spads, many of which were beginning to look like flying sieves from ground fire. The pilots were as worn out as the aircraft: on 16 September, Lieutenant John Jeffers of the 94th fell asleep while returning from a patrol. His Spad continued its flight on course, losing altitude slowly. Jeffers woke up in time to level out and crash on a hill not far from the airfield. He escaped injury.

Another short lull followed, as the American army redeployed for the Meuse-Argonne offensive. The 1st Pursuit Group rested and received replacements for the aircraft and pilots lost during the campaign. One noteworthy change of command occurred during this interval: on 25 September, Lieutenant Rickenbacker replaced Major Kenneth Marr as commanding officer ofthe 94th Aero Squadron.